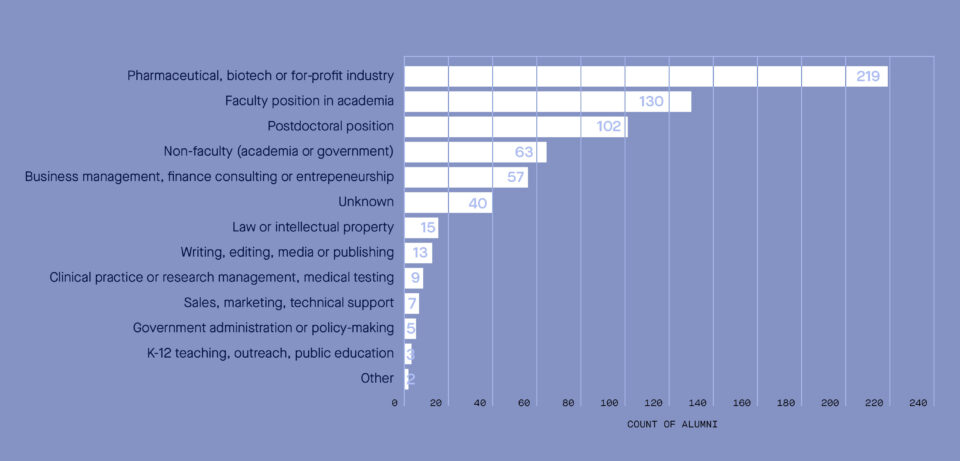

Alumni of the Skaggs Graduate School of Chemical and Biological Sciences at Scripps Research apply their education and training to a range of careers.

Vice President of Biologics

Travis Young, PhD, Calibr

Travis Young, PhD, completed his doctorate in chemical biology in 2010, and later joined Calibr, the drug discovery division of Scripps Research. He led Calibr’s development of a new T cell-based cancer immunotherapy, one of two cancer therapies that Calibr will soon move into clinical trials.

How did your experience as a grad student at Scripps Research influence your career?

Scripps Research offers an unparalleled focus on research which provides the time and resources to accelerate training. The environment of experienced research staff and postdocs here at Scripps Research fosters the development of critical thinking skills. For me, these were very significant in shaping how I approached my science and ultimately my career.

You have bridged foundational and translational science. What is the trick to working in both areas?

The trick is to balance hypothesis-driven research with a drug discovery-oriented mindset, but committing to both sides of the equation can be very rewarding. It’s allowed us to move forward high-risk, high-reward programs and discover novel approaches that would otherwise be overlooked.

What will you be working on over the next six months?

This is a very exciting time for Calibr. We’re getting ready to move two potentially transformative immuno-oncology programs into human clinical trials next year. The first program, a bispecific antibody for prostate cancer, is a unique take on an antibody-drug conjugate, using unnatural amino acid methods developed by Pete Schultz’s group. The second is a universal cellular therapy program, developed at Calibr, and recently partnered with AbbVie. For both programs we’re building an outstanding team of basic and clinical researchers to get these programs to patients.

Senior Research Investigator

Emily Cherney, PhD, Bristol-Myers Squibb

During her graduate school years, Emily Cherney, PhD, worked with Scripps Research Professor Phil Baran, PhD, looking for innovative ways to build some of nature’s most complex molecules in the laboratory. After receiving her doctorate in chemistry in 2014, she joined the pharmaceutical company Bristol-Myers Squibb to apply her skills as a chemist to the search for new medicines.

What stands out about your experience as a grad student at Scripps Research?

I had the opportunity to focus completely on my research. I walked straight into the laboratory immediately after arriving at Scripps Research. Coursework ended after my first year, and I was never required to TA undergraduate courses. In hindsight, I now see what a privilege that was compared to what most other graduate students experience. In short, I never had to dilute my efforts.

What did you study? Any achievements during grad school you’re particularly proud of?

I studied natural product total synthesis: applying organic chemistry to make complex molecules made in nature from simple building blocks. Understanding the fundamentals of known reactivity and extrapolating them in new ways for use in the context of complex molecule synthesis was the best part of my work. My proudest moments were when those extrapolated ideas succeeded.

What is your focus at Bristol-Myers Squibb?

I am a medicinal chemist. The therapeutic area I work in is

immuno-oncology. Specifically, I pursue the discovery of small molecules capable of helping a patient’s own immune system recognize and attack cancer.

What attracted you to going into industry?

I remember a student left Scripps Research to go to medical school. At the time, he said (and I’m paraphrasing) he could spend his whole life working in industry and never discover a drug, whereas, he knew he’d be able to help at least one person if he became a doctor. I would counter that by saying that, even if I only discover one new medicine during my entire career, I may be able to help thousands or even millions of people.

Global Director of Health Policy

Phyllis Frosst, PhD, Seqirus

When Phyllis Frosst, PhD, graduated with a doctoral degree in biology in 2001, she wasn’t sure where her scientific career would lead. Now she’s the global director of Health Policy for Seqirus, a multinational influenza vaccine company. Here’s how her Scripps Research education equipped her for her journey.

How did you travel from biology to public policy?

At Scripps Research, I was president of the Society of Fellows, an organization that promotes professional and social exchange between postdocs and other scientists and discovered that I enjoyed leading that sort of interaction. My peers seemed to think I was good at it as well. Then, at a conference in Washington, D.C., I networked with some Scripps Research alumni and ended up applying for—and getting—a policy analyst position with the National Institutes of Health.

What are your current responsibilities?

I direct government affairs and global pandemic policy for Seqirus, the second largest influenza vaccine company in the world. We partner with governments to prepare for and mitigate the devastation of an influenza pandemic.

Any advice for today’s graduate students embarking on their

scientific journeys?

Think about what you enjoy doing as well as the subject area. Then talk to lots of people; most are happy to spend 30 minutes sharing their job experience. Your PhD has taught you how to analyze and solve problems, so there are lots of ways to have an incredible, meaningful and rewarding career whether you stay in academia or pursue a position outside of it.

Scripps Fellow

Michael Bollong, PhD, Scripps Research

Michael Bollong, PhD, started his undergraduate education as a premed student, but laboratory experience at Scripps Research drew him toward a career in science. Bollong completed his graduate studies in chemistry at Scripps Research in 2016, and is the first researcher to join the Scripps Fellows Program, which supports the next generation of scientific leaders in launching impactful careers.

What did you focus on during your graduate studies?

In my PhD work in Pete Schultz’s lab, I focused on identifying drug-like small molecules that can alter cell fate in the context of disease. This led to a number of interesting findings, including the development of a preclinical drug candidate for the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), a lung disease. We also discovered an important chemical connection between a cell’s sugar metabolism and its antioxidant response. This study uncovered a new drug target and mechanism for activating the antioxidant response to treat diseases like neurodegeneration.

What stands out to you from your time as a grad student?

What makes Scripps Research so special are its scientists. I look back fondly on the many discussions had and friendships made with my fellow grad students, as well as the chance to learn from my heroes in chemical biology. The fact I can continue working with these scientists as colleagues in my new role of Scripps Fellow is a real privilege.

Where do you plan to go with your research now?

My new lab is focused on using chemical genetics to solve essential problems in cell biology and to generate the chemical starting points for new drugs. We have an interest in identifying drugs which safely activate cellular defense mechanisms to various stressors like heat and heavy metals to intervene in neuro-degenerative and autoimmune disease. We are also searching for drug molecules that manipulate cell growth pathways so that we might be able to perform organ repair in diseases of unmet medical need like heart failure.

Director of Biology

Jacqueline Blankman, PhD, Abide Therapeutics

Since receiving her doctorate in chemistry in 2012, Jacqueline Blankman, PhD, joined Abide Therapeutics, a San Diego company founded on work from labs of two Scripps Research professors, Dale Boger, PhD, and Ben Cravatt, PhD. As director of biology at Abide, Blankman works on developing drugs that target an enzyme she worked on during her graduate research in Cravatt’s lab.

What did you focus on during your graduate research?

My thesis work focused on communication pathways within cells that rely on signaling lipids, molecules built from fatty acids. I first became interested in lipid biology when I worked at the biotech FFA (“Free Fatty Acid”) Sciences in San Diego after my undergraduate degree. The naturally occurring molecules in the body that activate cannabinoid receptors are lipids, which fascinated me. When I learned that Ben Cravatt was studying the activity of these lipid neurotransmitters through chemically and genetically inactivating their metabolic enzymes, I was immediately interested in joining his group.

What are you focused on at Abide?

Much of my thesis work centered around the generation and characterization of a mouse lacking one of the enzymes that regulate these lipids, monoacylglycerol lipase (MGLL), which is the target of the clinical program that I work on at Abide Therapeutics. I am the lead biologist on the ABX-1431 team, which is working to bring our first-in-class clinical MGLL inhibitor ABX-1431 all the way from the lab bench through clinical trials to one day treating patients with CNS and pain disorders. I lead the nonclinical development work on the program, which includes pharmacology, toxicology, drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics (DMPK) and clinical biomarkers.

Why did you decide to go into industry as opposed to pursuing

an academic position?

I seriously considered both options. When Abide chose MGLL as the target for its lead program, they approached me about the opportunity to join the company and develop a drug targeting the enzyme that I had spent years characterizing. It was an offer that

I couldn’t refuse!

Professor

Erica Ollmann Saphire, PhD, Scripps Research

Erica Ollmann Saphire, PhD, earned her doctorate in 2000 and has come full circle as a professor at Scripps Research, mentoring graduate students who represent the next generation of scientists. Her research, which bridges molecular biology, virology and immunology, is paving the way to developing vaccines and therapeutics to counter deadly viruses such as Ebola and Lassa.

What attracted you to Scripps Research for graduate school?

Infinite flexibility and the absence of boundaries. I began grad school at Stanford studying marine biology in Monterey, scuba diving every day. But structural biology caught hold of me. Being able to visualize the fold and motion of a protein in three dimensions was the most intellectually satisfying thing I had ever seen. I knew I had to do that. The dean, Bernie Gilula, knew who I was and called me on the phone. He said, “You can come tomorrow, and you can work on what you want.”

How did your experience in the graduate school influence your career path?

I found immunology and virology, disciplines that require us to consider things at both the molecular level and the organismal and population level. I learned that tenacity and grit are frequently all that stand between failure and success. And I was inspired by professors Dennis Burton and Ian Wilson. Ian has incredible attention to detail and command of the literature. Dennis bridged the way to opportunities and collaborations. Both agreed that when something was important, you need to be willing to take risks.

What are you focused on now in your research?

There is a change in the nature of Ebola virus research, and a fresh challenge. The virus has a whole other side to it, lurking in immune privileged sites, circulating subclinically or asymptomatically. We are no longer putting out fires, but instead approaching it in a more complex way to understand its immunology, its replication, its effect on populations. What we have done before and the tools for structural biology we have historically had are no longer adequate. In the movie Jaws, there’s a quote when they realize what they are up against: “We’re going to need a bigger boat.” My lab is building that boat.