Scripps Research scientists find creative ways to work, stay connected during pandemic

“Hey, you’re on mute!”

To many of us, those words have become all but expected as we engage in our third online meeting of the day from our home office—which very well may be the kitchen table. It’s also the case for hundreds of Scripps Research scientists who had to begin working from home after shelter-in-place controls were implemented in March due to the unfolding COVID-19 pandemic.

As labs got back up and running over the summer, researchers were still urged to work from home when possible or rethink lab schedules to prevent crowding. Even when working on-site, health requirements have reshaped everyday interactions—just as they’ve changed the way we go about grocery shopping or socializing with friends.

Yet, as you might expect from those who spend much of their career trying things that have never been done before, scientists have found creative ways to not only adapt to this new world, but to continue producing life-changing research and making meaningful connections with one another.

Sheltered Progress

For most laboratories at Scripps Research that were not focused on COVID-19, bench-side operations ceased during the first few months of the pandemic. This presented obstacles to predominantly experimental groups but also drove investigators to rethink the process and timeline of scientific discovery.

“Typically, we collect experimental data, draft an outline of the findings and refine it for publication,” says Keary Engle, PhD, assistant professor in the Department of Chemistry. “I’ve really pushed my students to think about the direction of their projects and draft their story so they can be very efficient when they’re in the lab.”

Just as working from home provided a fresh environment to inspire alternative experimental approaches, many researchers dedicated much-needed time to important aspects of everyday science.

“I’ve been able to analyze results, develop new hypotheses and prepare presentations to share my findings,” says Rebecca Berlow, PhD, a staff scientist in the Department of Integrative Structural and Computational Biology. “I know my colleagues have also been able to focus on the time-consuming process of applying for funding to keep these projects going.”

Needing little more than a high-speed internet connection and a selection of software tools, computational scientists were perhaps best positioned to work remotely. Some researchers organized informal computational biology or chemistry workshops, enabling the organic transfer of skills between trainees, as would normally happen in person.

Home Schooling

The Skaggs Graduate School of Chemical and Biological Sciences took an imaginative approach to fostering education remotely—both with existing graduate students and potential future scientists in the wider community.

For early-stage graduate students, all classes went virtual, with a further expansion of dynamic online tools for learners and instructors. For trainees a little further down the doctoral track, respite from long hours in the lab provided an opportunity for important thesis updates.

Some students even completed their biggest PhD milestone from home: the dissertation defense. Structural biologist Colby Sandate turned it to his advantage: “I have a roommate who’s a YouTube streamer, so she was extremely supportive in letting me borrow her equipment and help build my home setup,” he says. “With strategic lighting, multiple screens and a desk placed in the living room, the overall effect made me look somewhat like a news anchor.”

While many defending students missed seeing their proud advisors or committee members face-to-face, the virtual broadcast allowed for greater human connection in other ways.

“I had far more people watching the event online than we would have had space for in the lecture hall,” Colby says. “Some of these groups, like my family, were also able to hold small viewing parties. The fact that I no longer had to worry about getting friends and family to and from the talk probably made me a lot less nervous.”

Meanwhile, the Graduate School’s educators have hosted open-access virtual events for college undergraduates to join from around the world. The interactive webinars have taken on topics such as “Robotics in Drug Discovery” and “Exploring the Faculty Track,” highlighting career options. They also launched a virtual summer science competition for elementary, middle and high school students, geared toward minority groups that are underrepresented in STEM.

Finding a Routine

Who could have predicted that eliminating a long commute would take getting used to?

“I miss my morning and evening drives,” says postdoctoral researcher Matthias Pauthner, PhD, in the Department of Immunology and Microbiology. “Those drives were my transition phase into and out of the working mindset, so now I try to replace them with a podcast over coffee in the morning and a walk in the evening.”

For those with young infants or school-age children, establishing a new routine is not as seamless. “For my wife and I, our days are typically a series of online meetings and playing ping-pong with who is watching the baby,” says Engle via a Zoom call, as he entertains his infant son, Oliver. “It’s challenging to find those blocks of time to write papers or grants. It’s when he’s down for the night that we often find ourselves at full speed for three to four hours.”

As Scripps Research faculty, staff and students face similar but distinct challenges, this has been a time of mutual understanding and increased empathy, with individual and collective wellbeing as the number one priority. “We’re honestly just trying to survive and not be too hard on ourselves,” Engle says.

Distancing But Not Distant

A major part of the psychological resilience required as a researcher is the feeling of unity among colleagues. As social animals, substituting the most basic human interactions with a webcam has been a major adjustment. Several principal investigators are mindful of striking a balance between not enough and too much videoconferencing.

To keep the camaraderie going, some labs planned virtual happy hours—complete with signature cocktails and a show-and-tell of quarantine hobbies.

“Game night is every Thursday,” says Scripps Research Fellow Danielle Grotjahn, PhD. “We’ve been playing interactive games like trivia and Pictionary, and the turnout has been great.”

Grotjahn’s team extended the invitation to other labs, which spurred a greater interest in new online social activities. “Some lab members have started a Friday night tradition of playing online Dungeons and Dragons,” she says.

Safely Reopening Research

Even though shutting down non-essential experiments caused disruption, ramping up brought its own challenges. Laboratories now have designated COVID-19 coordinators who review everyone’s experimental plans each week to ensure they conform with new health-focused policies laid out by the institute’s leadership.

“It’s absolutely a work in progress,” says Mildred Kissai, a graduate student in the Department of Chemistry. “To reduce density in the lab, half of us agreed to the morning shift, with the remaining members on the afternoon shift.” Many smaller workspaces have been rearranged for greater social distancing and common-space furniture is, for the time being, gone.

As on-campus activities expand, new procedures help prevent the spread of COVID-19. Employees who work on-site submit a daily certification of health prior to arriving to campus and are screened for COVID-19 weekly. Temperatures are checked prior to entering buildings. Such activities are quickly becoming second nature to scientists.

Reacclimating to an environment that warns against having lunch or close conversation with colleagues may instead be the greater ordeal. Nevertheless, members of the Scripps Research community are taking each new change in stride, enthusiastic to return to the life-changing science they love. “In the grand scheme of things, a lot of us are in a privileged position,” notes Engle. “We know there are so many people who are facing significant insecurities in both health and finances, so we must keep that in perspective.”

This position of gratitude echoes throughout the institute, encouraging researchers to reframe new scientific challenges as opportunities for growth.

The Crisis Management Team

The Crisis Management Team at Scripps Research mobilized early in the pandemic to guide the institute’s response to an ever-evolving COVID-19 landscape. The team has implemented science-based policies to protect the Scripps Research community while supporting critical ongoing research into COVID-19 and other diseases. Led by Chief Operating Officer Matt Tremblay, PhD, the team is comprised of leadership from several departments:

Jamie Williamson, PhD, Exec. Vice President, Research and Academic Affairs

Karen Haggenmiller, Vice President, Human Resources

Megan Young, Director, Operations

Alanna Rutan, Esq., Compliance Counsel, Operations

Anna-Marie Rooney, Vice President, Office of Marketing and Communications

Chinh Dang, Chief Information Officer, IT Services

Douglas Bingham, Esq., Executive Vice President, Florida Operations

Scripps Research Professor Kristian Andersen, PhD, a genomic epidemiologist, has provided weekly scientific briefings on the pandemic to the team. He continues to provide guidance on the implementation of best practices, in addition to serving as a leading advisor for government and public health officials. The Crisis Management Team receives assistance and guidance from other faculty and staff from both the Florida and California campuses.

Business Not As Usual

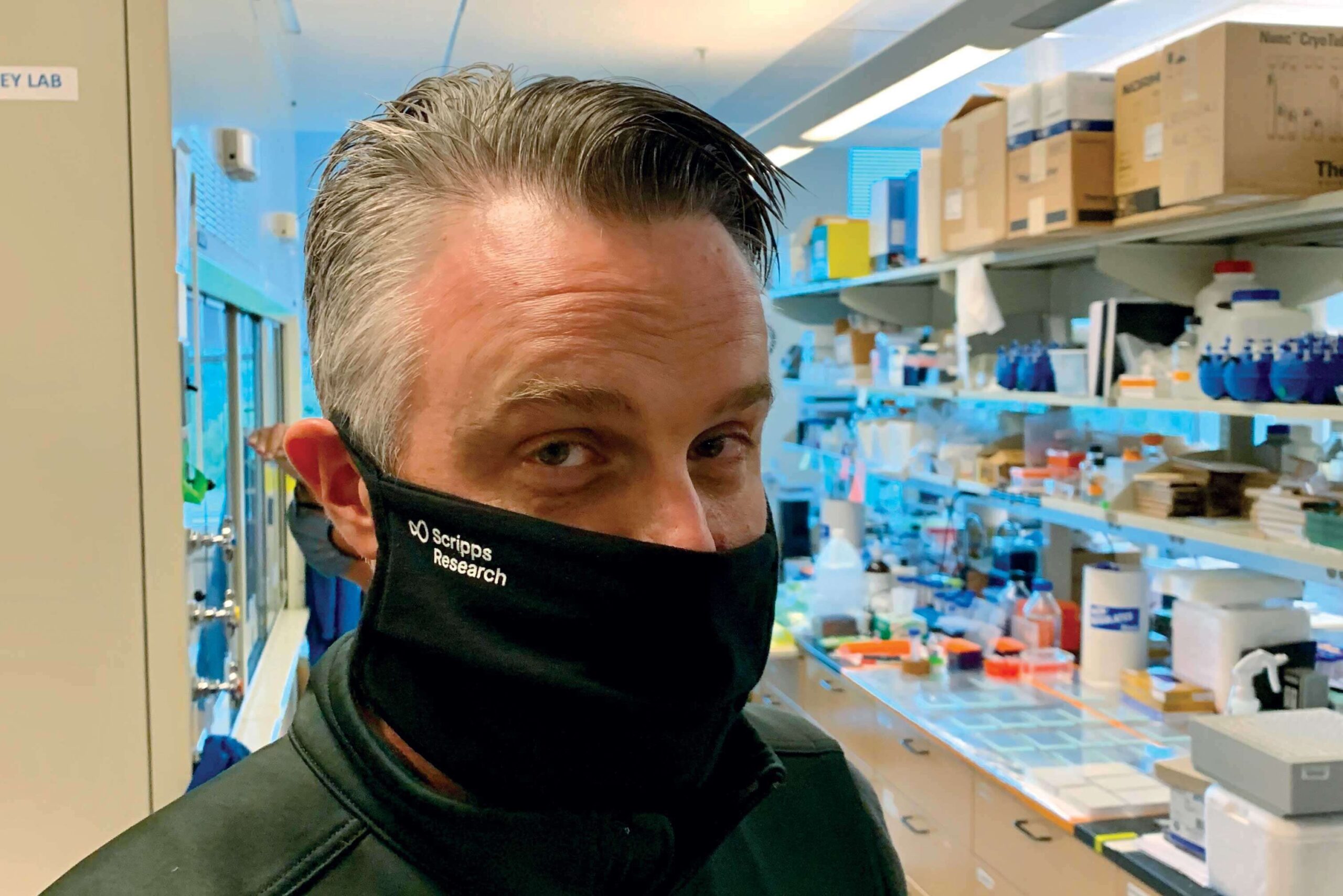

They mask up and show up. When Scripps Research closed its La Jolla and Jupiter campuses in March to all but the most critical scientific and administrative operations, a small cadre of employees continued to do their jobs on-site—many of them taking on added responsibilities as the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded.

“As a Level 3 safety manager, I basically have my finger in each lab working with biological agents, recombinant DNA, things like that. We regularly audit labs to make sure they are in compliance with the National Institutes of Health’s safety guidelines. My job really is to facilitate research and make sure it’s done safely. ”

—Laurence Cagnon, PhD

Biosafety Manager, Environmental Health & Safety – 12 years at Scripps Research, California

—Dawn Kimball

Site Coordinator, Shipping & Receiving (contracted through Avantor Science) – 8 years at Scripps Research, California

—Rachel Martin

HR Analyst, Human Resources – 3 years at Scripps Research, Florida

—Mark Van Hoy

Supervisor of Facilities and Engineering – 12 years at Scripps Research, Florida