There’s power in numbers. Even if the number is just two.

This is what Courtney Miller, PhD, learned early in her career when she met another female researcher, Ghazaleh Sadri-Vakili, PhD.

“We were both postdocs and both exploring epigenetics in neuroscience, something very new at the time,” says Miller, now an associate professor of neuroscience at Scripps Research. “I raised my hand and asked about a technique she’d described. It was something I wanted to learn but had been told it was too difficult to teach. Ghazaleh said, ‘Come up to MassGeneral and I’ll teach you.’”

Miller and Sadri-Vakili, now director of neuroepigenetics at the MassGeneral Institute for Neurodegenerative Disease, became friends and came to realize they had both experienced numerous challenges as female scientists and that neither had scientific mentors who were women.

“We decided that had to change,” says Miller. “Even though we were young, we decided to take action.”

Overcoming the hurdles to diversity

Study after study has demonstrated that diverse groups—those comprising a mix of gender, race and ethnicity—are more innovative in their thinking, thereby producing more impactful scientific discovery. Yet women continue to be underrepresented in the STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) fields, especially at the upper levels.

Multiple factors stack the deck against women and underrepresented minorities in the life sciences. The momentum of numbers, for one. Faculty and leadership positions at universities and other research institutes have been overwhelmingly held by white males, at least until recent years. This means that decisions on hiring and promotions were made by men who, whether consciously or not, may have favored other men. Across the industry, males continue to be paid more than their female peers and are promoted sooner.

“There are many levers one can pull to better support girls and women as they move through their educations and careers, and we want to make sure we’re pulling all the ones we can.”

—Donna Blackmond, PhD

Co-chair, Chemistry Department

Scripps Research

This bias extends to other important aspects of science. Studies have shown that reviewers given identical resumes still tend to rate a man as being more highly qualified for a scientific position than a woman. And, of course, biology presents a high hurdle. Women who decide to start a family must step out of the lab and then, according to a number of studies, usually shoulder the majority of the responsibilities at home.

While they were long denied positions of leadership, however, women are now heading the change to make science more diverse.

Taking the lead

If you want to solve a complex problem, put a scientist on it. That’s what Scripps Research did when assessing its own record and practices around gender equity in hiring and promoting women faculty. Three years ago, Donna Blackmond, PhD, co-chair of the chemistry department at Scripps Research, was named to head a committee to examine the issue and identify ways to create the best possible environment for anyone pursuing scientific research at the institute.

At Scripps Research, the Gender Parity Committee worked with institute leadership to ensure equal pay for equally qualified faculty members. The committee discovered that salaries and time to promotion were equal for male and female faculty members at Scripps Research. To bolster the overall number of women faculty members, the committee recommended that the institute accelerate efforts to recruit women early in their scientific careers. Another recommendation: Make every effort to increase faculty diversity while maintaining academic excellence.

“The challenge of women in science extends from early education all the way to retirement,” says Blackmond. “There are many levers one can pull to do a better job of supporting girls and women as they move through their educations and careers, and we want to make sure we’re pulling all the ones we can.”

Advocacy in numbers

One important lever is the support from peers, an invaluable resource for women scientists at any stage of their careers.

On the California campus of Scripps Research, the Network for Women in Science (NWiS) helps fill that role. “We define challenges that disproportionately affect women here, then create conversations about how to implement change,” says the group’s advocacy co-chair Sophie Shevick, a student at Skaggs Graduate School of Chemical and Biological Sciences at Scripps Research. “Our current goals include ensuring that every building has a gender-neutral bathroom as well as a lactation room.”

February 11, 2020

International Day of Women and Girls in Science

Acknowledging that science and gender equality are both vital for the achievement of the world’s development goals, the United Nations established the International Day of Women and Girls in Science in 2015.

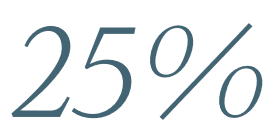

While more women than men currently earn degrees in STEM fields (encompassing science, technology, engineering and mathematics), according to a 2017 report by the U.S. Department of Commerce, only 25 percent of these gifted graduates end up actually working in STEM occupations. Scripps Research is working to change that.

The group hosts panels on pertinent topics, such as parental leave and sexual harassment, as well as coffee hours for informal discussion. In addition to advocating for career scientists, NWiS members inspire young science enthusiasts. Millie Kissai, another student in the Skaggs Graduate School, coordinates the group’s many outreach activities, including partnering with DETOUR, an organization that “introduces girls of color to fields they are not typically exposed to.” Last spring, she and her fellow researchers taught a group how to extract DNA from strawberries, a hands-on experience met with infectious enthusiasm, Kissai says.

On its Florida campus, Scripps Research is hosting a series of fundraising events designed to establish a fellowship for a woman student enrolled in its Skaggs Graduate School. The Women in Science Education (WISE) initiative launched last year and, in February, a symposium aligned with the International Day of Women and Girls in Science celebrated the many achievements of the institute’s scientists while pointing to a bright future.

“We define challenges that disproportionately affect women here, then create conversations about how to implement change.”

—Sophie Shevick

Advocacy Co-Chair

Student, Skaggs Graduate School of

Chemical Biological Sciences

Scripps Research continues to diversify its faculty. Of five junior faculty members hired in July 2018, four are highly accomplished women from varied disciplines. Jamie Williamson, PhD, executive vice president of Research and Academic Affairs, says, “These scientists are demonstrating incomparable talent across some of the most pioneering areas of current research. They represent the future of Scripps Research.”

Peer power

The push to bring more women into science isn’t just about achieving balanced numbers and employment equity. As more women direct their own labs and programs, research heads into unexplored areas, often ones that impact women’s health.

Jennifer Radin, PhD, a researcher at the Scripps Research Translational Institute, for example, is working to fill the knowledge gap about the physiological changes that occur during pregnancy and how those changes vary by race, age and pre-existing conditions. Pregnant women remain one of the least studied populations in medical research, even while maternal morbidity and mortality rates in the United States are on the rise.

Radin directs the POWERMOM study, which uses digital technologies to gather health data from a diverse group of pregnant women. Participants in the study can compare their data with peers and receive individualized feedback. “We’re hoping this will be a multi-decade research project that will empower pregnant women in their own health and help researchers understand how to improve the health of expecting mothers and babies,” says Radin.

Another example of how women are pioneering research of particular relevance to women is the work of Hyeryun Choe, PhD, a Scripps Research professor in the Department of Immunology and Microbiology. When the Zika virus emerged in Brazil in 2015 and began spreading, doctors and scientists didn’t know how the virus caused microcephaly and other severe birth defects. Choe was the first to uncover the details behind the Zika virus’s unique ability to cross the placental barrier and expose a fetus to multiple health dangers.

Working for change

As for Courtney Miller, her conversations with Ghazaleh Sadri-Vakili led her to reflect early in her career on her own experiences as a female scientist—and spurred her to action.

Now she and Sadri-Vakili make it a priority to educate and encourage women scientists through a bimonthly blog and in-person gatherings. At the annual Society for Neuroscience conference, they host a “Breaking Barriers for Young Women in Science” event and recruit top researchers to lead a panel discussion then interact with the early-career attendees.

Invariably, hundreds flood the room. The questions vary by experience, says Miller, but range from how to overcome assumptions that women are less talented to how to balance career and family life. Seasoned scientists often want to discuss implicit biases against women in the sciences.

Miller tells women that she has never accepted the status quo in her field that favors male scientists, and they shouldn’t either.

“Everyone develops their own style for dealing with it,” Miller says. “Some endure it. Some work to change it. I’m doing what I can to change it.”