Celebrating a century of Science Changing Life

Scripps Research scientists have spent a remarkable 100 years pushing the boundaries of biomedical innovation. Now, as it celebrates its centennial year, Scripps Research is building upon its exceptional past to expand its global impact. The institute is empowering world-renowned scientists to pursue groundbreaking ideas for the most pressing problems in human health: cancer, heart disease, deadly pathogens, neurological diseases and much more.

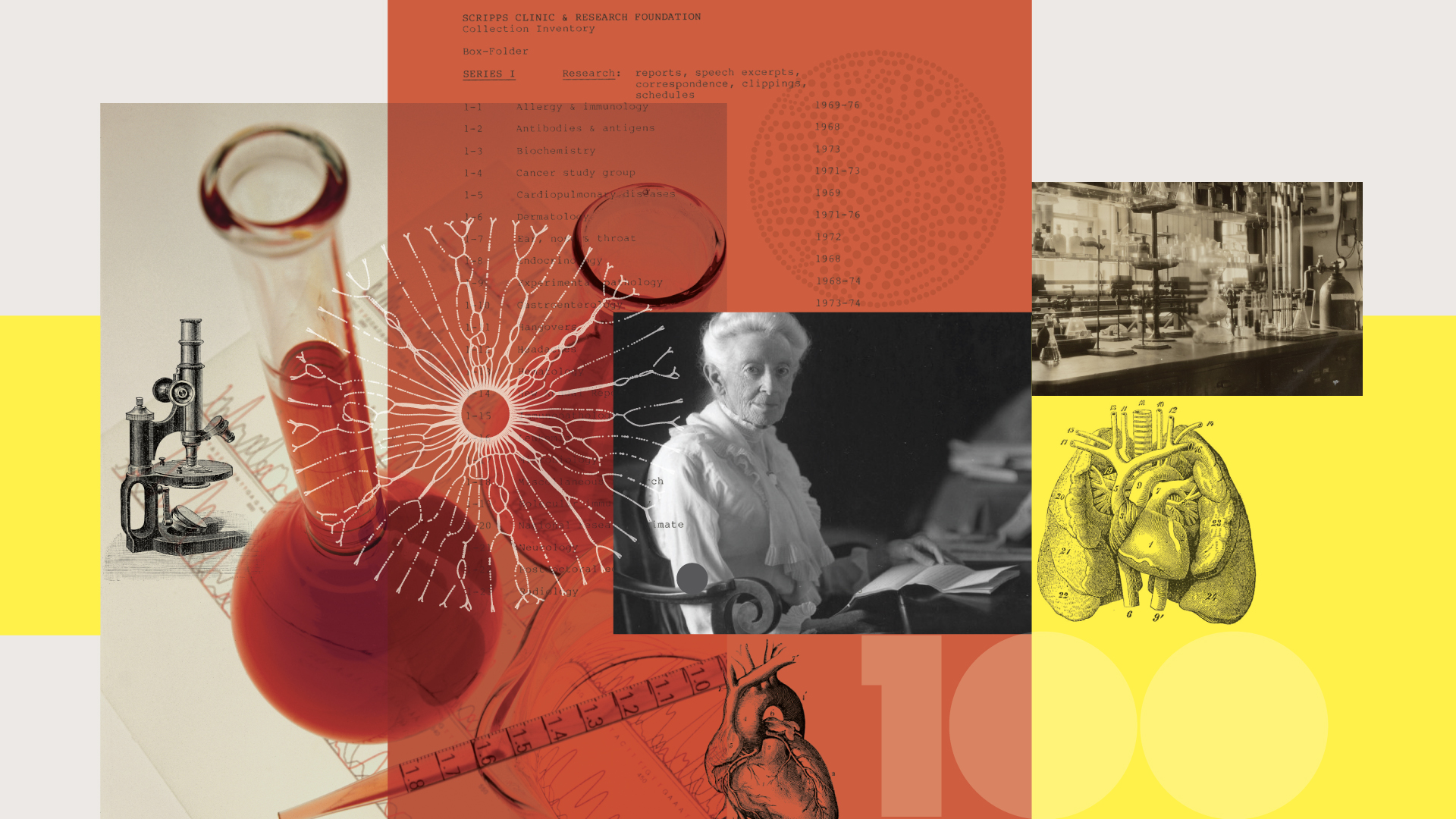

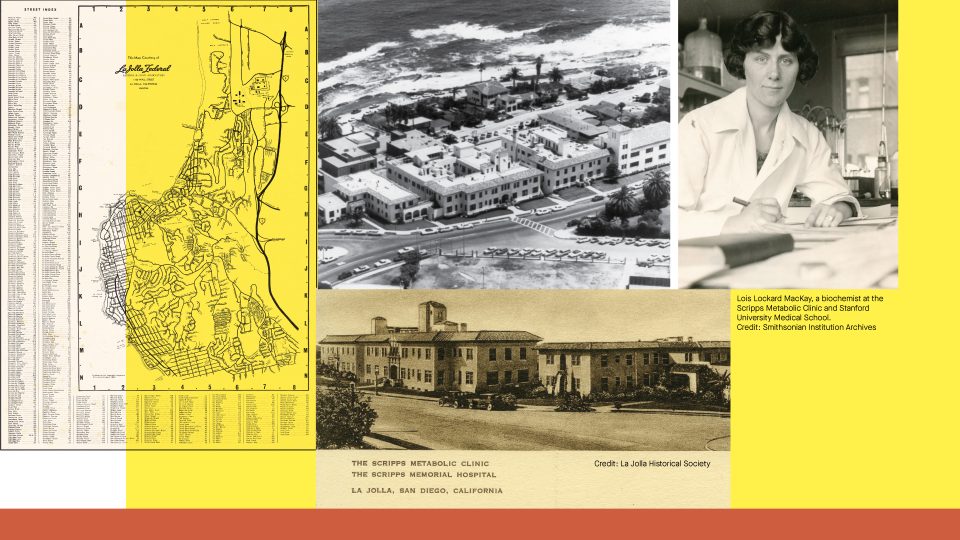

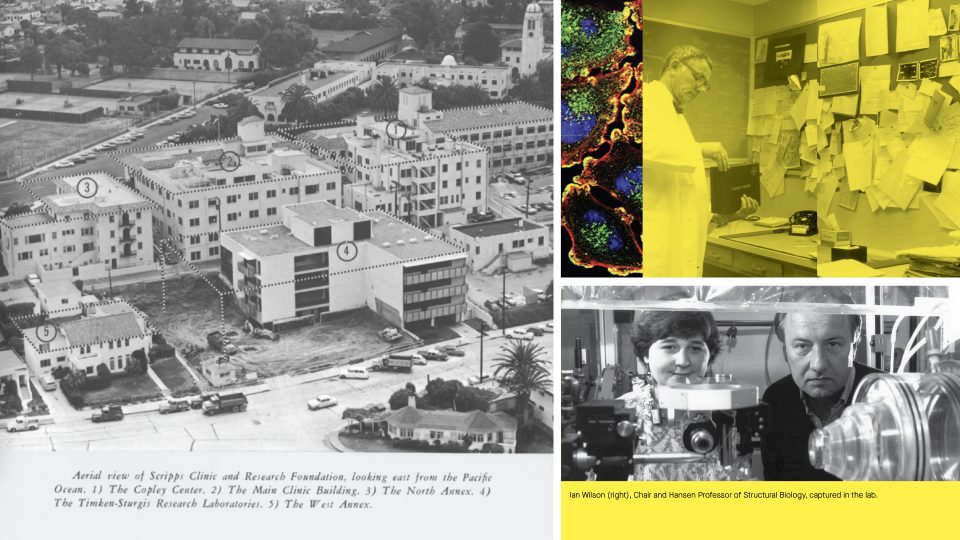

Scripps Research began as the Scripps Metabolic Clinic in 1924 in La Jolla, California.

Credit: La Jolla Historical Society

Walking through a century of impactful science

Ellen Browning Scripps was feeling restless. After slipping on the porch of her oceanfront home in downtown La Jolla, she was confined to a small, shared hospital room. She found herself in a 10-bed healthcare facility with a broken hip and a mounting frustration with the poor medical infrastructure of La Jolla at the time—specifically, January 1922.

Ellen Browning Scripps had already witnessed what modern science and medicine were capable of, thanks to the 1921 discovery of insulin. Multiple members of her family were afflicted with metabolic disease—or, in modern medical terminology, diabetes—and she had seen firsthand how a scientific breakthrough could fundamentally transform people’s lives. Throughout her life, she had watched numerous loved ones perish from diabetes and complications of the disease, but with insulin, there was the possibility to lead a typical, healthy life. And it was all thanks to scientific research.

In Ellen Browning Scripps’ eyes, this scientific progress was miraculous. While receiving treatment for her hip, she urgently wrote to her half-brother, E.W. Scripps, “My latest adventure will have to be, I think, a new hospital building.”

She had learned the ‘art of giving.’ But in her simple life in La Jolla, fronting the Pacific, she showed that she had also learned the art of living.

THE NEW YORK TIMES OBITUARY: ELLEN BROWNING SCRIPPS (1836 – 1932)

In December 1924, she and her brother founded the Scripps Metabolic Clinic in downtown La Jolla. The clinic, which would later become Scripps Research, was a research facility dedicated to investigating and treating diseases, with a focus on diabetes. By this time, Ellen Browning Scripps had already found success in multiple pursuits: as a schoolteacher, a journalist and a newspaper mogul. But she realized that investing in science would usher in the future of medicine—across both San Diego and the world.

And she was right.

A century later, Scripps Research has made countless seminal discoveries toward improving human health around the globe. Beginning with Ellen Browning Scripps’ vision, many factors led Scripps Research to become what it is now: one of the world’s preeminent independent nonprofit biomedical research institutes.

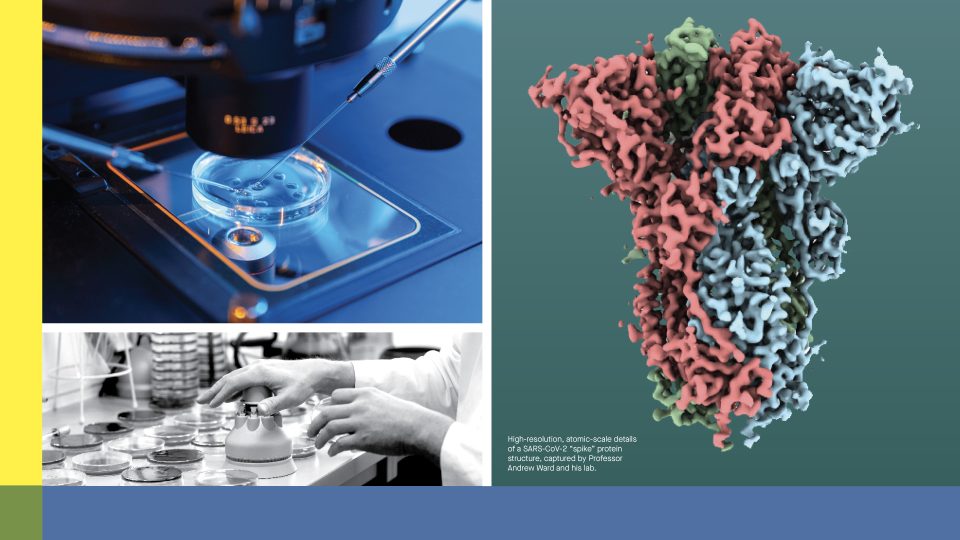

The institute’s renown is evident when walking around the campus on Torrey Pines Mesa today. If you head over to the Department of Immunology and Microbiology, for example, you may meet scientists developing universal vaccines for influenza, HIV and coronaviruses. A quick walk through the Nelson Tunnel to the Department of Integrative Structural and Computational Biology will lead you to where researchers revealed the first structure of a human coronavirus spike protein—critical information used in making the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines. Right next door, students at the top-ranked Skaggs Graduate School of Chemical and Biological Sciences are training to become the next generation of scientific leaders.

Down North Torrey Pines Road, scientists at Scripps Research’s Calibr-Skaggs Institute for Innovative Medicines are advancing a broad pipeline of medicines. They work closely with chemists and biologists at the Beckman Center for Chemical Sciences and the Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology, where researchers study and harness life’s chemical building blocks to develop life-changing therapies and tackle global sustainability challenges.

Across the street at the Dorris Neuroscience Center, established through donations by philanthropist and former university professor Helen Dorris, scientists are shedding light on the “black box” that is the brain, helping us understand the mechanisms behind why we age, what drives neurodegenerative diseases, how we perceive touch and more. Meanwhile, the Scripps Research Translational Institute, led by Eric Topol, The Gary and Mary West Chair of Innovative Medicine, continues to pursue novel solutions for individualized medicine across a range of health conditions and diseases. This includes spearheading the All of Us Research Program—an effort to build one of the largest, most diverse health resources of its kind.

It’s clear that Scripps Research has grown immensely during the last 100 years, much like the rural landscape of Ellen Browning Scripps’ La Jolla (which is now home to parks, buildings, hospitals and an aquarium with the Scripps name). But through its many changes and evolutions, the institute has remained true to her original vision of making science matter and creating a better, healthier future for all.

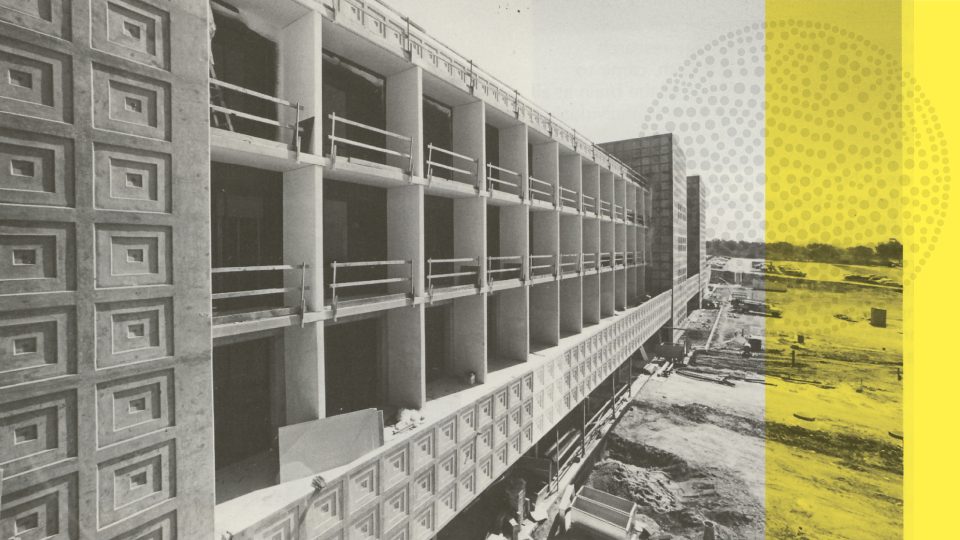

The first building of the Scripps Clinic and Research Foundation constructed at the Torrey Pines site in 1974-76.

Laying a strong scientific foundation

Scripps Research currently houses six academic departments and two translational research divisions, which work closely together to uncover discoveries capable of transforming human health. This is all made possible by the strong basic science foundation the institute sits upon, built over the course of a century.

After the Scripps siblings founded the Scripps Metabolic Clinic, physicians performed their research and treated patients. The clinic prospered and expanded over the years, eventually becoming the Scripps Clinic and Research Foundation in 1956. Its new, formalized mission was to pursue clinical and basic investigations into the origins and development of human disease.

“The advantage [of Scripps Research] is we’re allowed to spend almost 100 percent of our time in research,”

Michael Oldstone: FORMER SCRIPPS RESEARCH PROFESSOR EMERITUS AND POSTDOC FELLOW (DIXON LAB)

This focus expanded in 1961, when pioneering immunologist Frank Dixon moved his lab from the University of Pittsburgh to the institute. He and others, like professor emeritus Charles Cochrane, were drawn to the freedom to pursue research outside of the traditional administrative constraints of the university they were accustomed to. Dixon and Cochrane were joined by three of their colleagues, a large group of postdoctoral researchers, a few staff members and many ideas about where the future of science could lead to. They established the Department of Experimental Pathology to uncover the role the immune system plays in health and disease. By 1975, the institute had outgrown its space in downtown La Jolla and begun moving its campus to Torrey Pines after 13.2 acres of undeveloped land was donated by the Dow Chemical Company.

“The advantage [of Scripps Research] is we’re allowed to spend almost 100 percent of our time in research,” said former Scripps Research professor emeritus and postdoctoral fellow in Dixon’s lab, the late Michael Oldstone, in a 2009 interview.

Dixon went on to serve as director of the institute, where his immunological focus forever shaped its scientific direction. At Scripps Research today, immunologists and structural biologists work together to develop vaccines for infectious diseases such as influenza, HIV, COVID-19 and Lassa fever. Researchers are also uncovering critical information about the innate and adaptive immune systems, including how global infectious disease threats infect and spread through a population. This is also revealing key insights into the basis of autoimmune diseases—like diabetes, the institute’s original focus—as well as neuroimmune diseases like atopic dermatitis and the fundamental immune mechanisms of cancer. Scientists at the institute have also been responsible for developing antibody technologies, which have enabled multiple therapies that are approved today.

The overarching goal of our studies, as Department of Immunology and Microbiology Chair Dennis Burton notes, is to understand how our immune system operates and design medicines to prevent or control deadly diseases.

The right chemistry

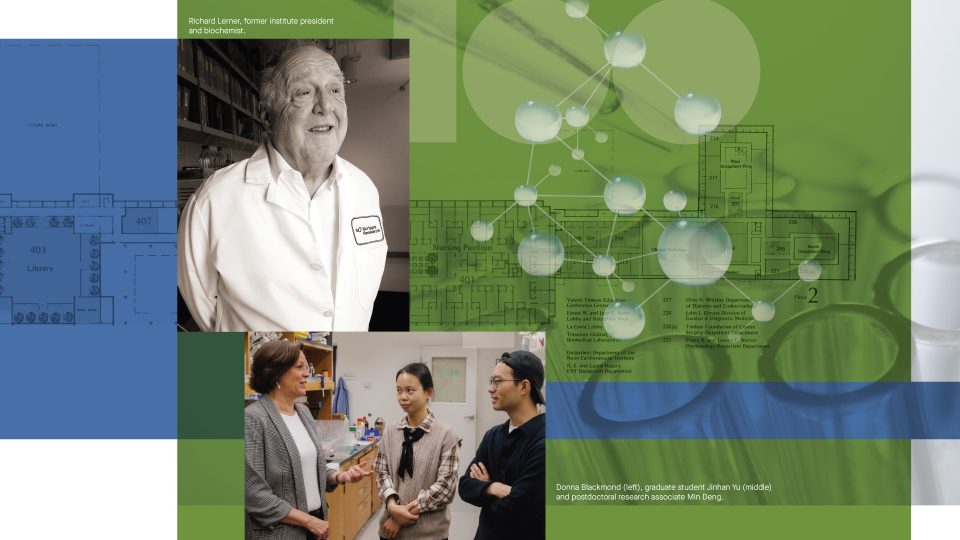

The institute’s reputation for instilling scientific excellence, collegiality and cross-disciplinary collaboration attracted biochemist Richard Lerner to the Department of Experimental Pathology. Beginning as a postdoctoral fellow in 1965 and returning as a faculty member in 1970, Lerner would go on to serve as the institute’s president from 1987 to 2012, leaving a legacy that is still very much felt at Scripps Research today.

Lerner realized that chemistry and biology are inextricably linked, and that studying their connections would unlock a new era of science and medicine. During his tenure as president, he started the institute’s Department of Chemistry, attracting top talent from around the world and establishing the institute as a leader in chemistry and chemical biology.

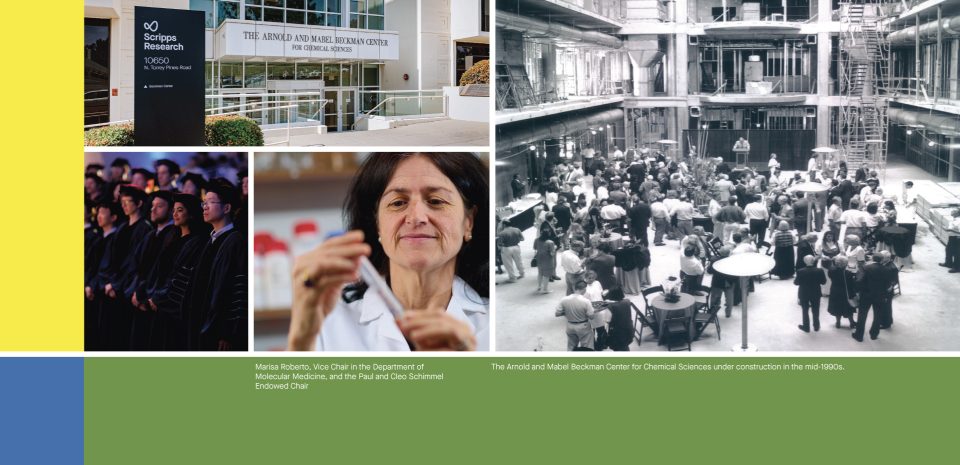

Scripps Research is now home to some of the world’s leading chemists across organic chemistry, synthetic biology, chemical biology and more, who are advancing our ability to design and produce molecules, develop new medicines and address climate change. This includes the development of “click chemistry”—an ingenious method for building molecules—pioneered by W.M. Keck Professor of Chemistry K. Barry Sharpless. In 2022, Sharpless received his second Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his groundbreaking research in this area, after receiving the 2001 Nobel Prize for his work on chirally catalyzed oxidation reactions.

“Everything in the world is made up of molecules, and we have some of the best people in the world who know how to synthesize those molecules and carry out groundbreaking research,” says Donna Blackmond, professor and The John C. Martin Endowed Chair in Chemistry. “One colleague and I met at the coffee cart, and it turned into two papers that we wrote together. I haven’t found that kind of collaborative atmosphere anywhere else I’ve been.”

In 1996, the Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology was established at Scripps Research through a gift from Aline and L.S. “Sam” Skaggs to foster research projects at the intersection of chemistry and biology. This focus remains one of the institute’s core building blocks and has proved to be fertile ground for generating medical advances. Discoveries made in Scripps Research labs have led to 15+ FDA-approved therapies, which have transformed—and in certain cases even saved—countless lives, and they will undoubtedly continue to do so in the century to come.

When premature infants struggle to breathe, they are given a life-saving medicine that originated at Scripps Research, Surfaxin®. When patients are diagnosed with conditions such as heart disease, multiple sclerosis and arthritis, they often receive medicines that Scripps Research either developed or enabled (Vyndaqel®, Zeposia® and Humira®, respectively). When the COVID-19 pandemic began, Scripps Research discoveries were critical to the rapid development of vaccines that protected hundreds of millions of people worldwide.

A scientist and an entrepreneur, Lerner also cultivated relationships with industry executives in the pharmaceutical world—unusual at the time due to a culture of keeping industry and academic enterprises separate. This foresight helped shape San Diego’s life-science sector into the thriving ecosystem it is today. Torrey Pines Mesa is now an epicenter of collaboration among academia, nonprofits and industry that takes promising science from the lab bench to the clinic. In fact, numerous biotechnology companies in the region were founded by Scripps Research scientists.

“We felt we were with him on a nonstop adventure,” says Paul Schimmel, a professor in the departments of Molecular Medicine and Chemistry who Lerner recruited. “Like pioneers of the Old West who would transform medical research and its associated graduate education.”

The Skaggs Graduate School of Chemical and Biological Sciences was also established during Lerner’s tenure, in 1989. Since its founding, the graduate school has consistently ranked among the top 10 in the nation for PhD programs in Chemistry and Biological Sciences. It currently enrolls approximately 400 students across programs at the interface of chemistry and biology who work with professors, mentors and advisors during their doctoral journey.

Over the last three decades, the graduate program has conferred more than 900 doctoral degrees, and many of the recipients are now national and international leaders in the academic and industrial life science sectors. Around 30 percent of graduates of the doctoral program pursue careers in academia, with Scripps Research alums serving as faculty members at Harvard, MIT, Stanford, Yale, Oxford and other leading universities. Leveraging their training in translational research, more than half of graduates pursue industry careers, mostly at pharmaceutical or biotechnology companies.

A new century of innovative science and medicine

Peter Schultz became CEO in 2015 and was named President the following year. Throughout his career as a researcher and chemist—which includes game-changing discoveries like catalytic antibodies and an expansion of the genetic code—he had seen the ways that promising science could get lost in the gap between the lab bench and the clinic. This “Valley of Death,” as it’s proverbially known in the biopharmaceutical industry, is where research stagnates due to lack of funding or resources.

Schultz, who is the L.S. “Sam” Skaggs Presidential Chair, made it his mission to build on the institute’s historical success in generating new medicines, but with intention and scale, where promising ideas can rapidly make their way into the drug discovery and development pipeline. This is also why he launched Calibr (now the Calibr-Skaggs Institute for Innovative Medicines) in 2012. As the drug discovery arm of Scripps Research, Calibr-Skaggs has dozens of therapies in clinical and preclinical development, many of which originated in Scripps Research labs.

“It’s not about money—it’s about time,” Schultz once said in an email to a Calibr staff member. “We need to move as fast as humanly possible—

or faster.”

This reflects the new model Schultz is building at Scripps Research: foundational research seeds drug discovery, new candidate medicines are developed and advanced through preclinical and early clinical trials by the institute itself, strategic alliances are formed with pharmaceutical companies to bring these novel medicines to market, and subsequent royalties are reinvested in basic research. It’s a model that can sustain itself while pushing past the current boundaries in drug development to ensure that discoveries made in basic science are followed to their full potential.

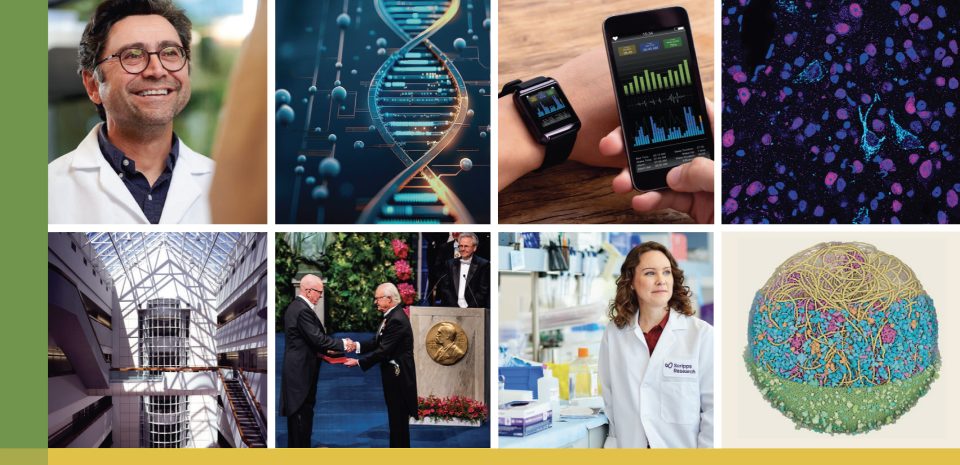

Top right: New method in Professor Li Ye’s lab shows where drugs hit targets in the body

Bottom center left: Nobel laureate Barry Sharpless receiving his second Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2022

Bottom center right: Kristen Johnson, senior director of discovery biology, Calibr-Skaggs

Bottom right: Model of a Mycoplasma Cell by David S. Goodsell, professor of computational biology

“At Scripps Research, we talk about what the big problems are, and what are the big contributions we could make that would be of that magnitude,” says Hollis Cline, Hahn Professor of Neuroscience and director and chair of the Dorris Neuroscience Center in the Department of Neuroscience. “The institute supports this type of research, which is how great breakthroughs are made—by taking risks and pursuing ideas that are out of the normal range.”

The institute’s focus on impactful, translational research is evidenced by recent and ongoing discoveries. For example, neuroscience professor Ardem Patapoutian was awarded the 2021 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for solving how the brain perceives touch and other mechanical stimuli. These findings are now helping researchers uncover fundamental aspects of disease pathology and novel drug targets. Meanwhile, at the Scripps Research Translational Institute, scientists and clinical investigators are uncovering the specific genetic, behavioral and lifestyle factors that contribute to overall well-being, with research spanning cardiovascular health, infectious diseases, sleep medicine and more.

The institute’s translational emphasis continues to grow with the campus. In the second half of 2024, scientists and research teams will be moving into the new Chi-Huey Wong Laboratories for Biomedical Research building, generously donated by philanthropist and businessman Samuel Yin. This group will span different departments, but all will be focused on making discoveries in basic areas of science that translate into new medicines, processes and therapies.

“Scripps Research has a rich tradition of fearlessly pushing scientific frontiers and overcoming institutional barriers. As we move into the next 100 years, we hope to reinvent the research institute model to expand the global impact of Scripps Research on science, medicine and the public.”

PETER SCHULTZ: PRESIDENT AND CEO, SCRIPPS RESEARCH

When Ellen Browning Scripps founded the institute in 1924, she held the vision of advancing scientific research to not only extend life but also improve it. She once said, “The most important and beautiful gift one human being can give to another is, in some way, to make life a little better to live.” These words still echo and resonate throughout the Scripps Research campus today, as the institute charts its course into a new century of science that changes lives.