A new process from Scripps Research has an immediate impact on drug discovery by making complex molecules easier to build.

When chemists struggle to connect carbon-based molecular fragments—the building blocks of drugs—into the right 3D shapes, promising medicines get stuck on the drawing board, never progressing beyond the lab. Recently, back-to-back studies in Science and Nature from Scripps Research reveal a faster, cleaner way for chemists to build complex, 3D molecules, including shapes that were once considered impossible to assemble using straightforward radical methods. Such techniques harness short-lived, highly reactive molecules called radicals to form chemical bonds. By simplifying the tools needed to join carbon atoms and preserve a molecule’s delicate 3D structure, this work lays out a practical blueprint to make drugs more easily at a lower cost and with less waste.

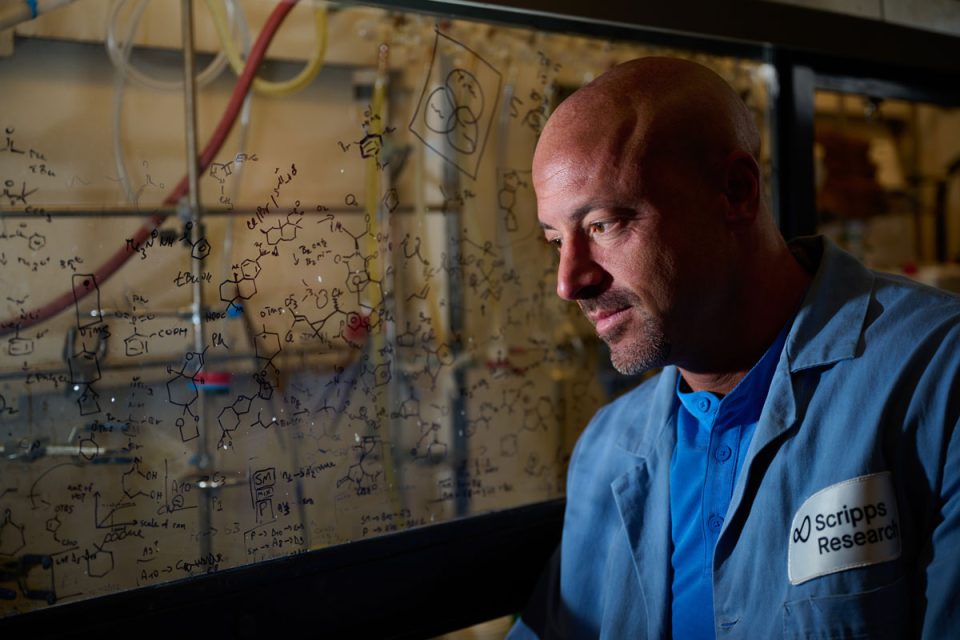

“This chemistry is a step in the direction of democratizing access to the most complicated molecules,” says Phil Baran, the Dr. Richard A. Lerner Endowed Chair at Scripps Research and the senior author of both studies.

From radical to reliable

For decades, the world of drug discovery has relied on a core set of carbon–carbon bond-forming reactions to snap molecules together like LEGO bricks. These reactions link carbon atoms into the frameworks that form everything from medicines to plastics and other everyday materials. Among the gold standards since the late 1970s is the Suzuki coupling: a Nobel Prize-winning chemical method developed by Akira Suzuki that’s now so reliable and easy to run that chemists call it downright boring—and they mean this as the highest praise.

“A boring reaction is a useful one,” explains Baran. “It’s simple to run and performed in labs across the world.”

Despite its strengths, the Suzuki coupling works best with 2D, ring-shaped systems. It struggles when chemists need to “escape from flatland”: a phrase they use to describe building more 3D, saturated carbon frameworks (sp³-rich molecules). In this case, “saturated” means the carbon atoms are fully bonded to other atoms with single bonds only—no double or triple bonds—making the structure more 3D and flexible.

But another method called radical cross-coupling, which also dates to the 1970s, does what Suzuki can’t: It fuses saturated, sp³-rich fragments that bend, twist and wrap around protein pockets in ways simple rings aren’t able. This is what often gives modern drugs their potency and selectivity.

Think of it like this: Traditional methods such as the Suzuki coupling are great for snapping together molecules that have the simplicity of flat LEGO pieces. By contrast, radical cross-coupling has the potential to connect more complex, 3D fragments—akin to intricate LEGO sculptures shaped like real drug molecules.

Still, the strategy traditionally came with operational barriers: harsh chemicals, excess metal powder (like zinc shavings), elaborate photochemical or electrochemical setups, and scale-up challenges. Baran’s lab tackled this conundrum by creating an approach that makes radical cross-coupling practical with Suzuki-level ease.

But if this radical method is so simple, why wasn’t it discovered sooner? Because making cross-coupling truly practical meant reimagining the whole setup—from how radicals behave to how the reaction is triggered.

In one study, published in Science in March 2025, Baran and his colleagues devised a universal, redox-neutral method for radical cross-coupling—a technique that allows for a balanced exchange of electrons as they shuffle around molecules, meaning harsh chemical additives and specialized gear aren’t needed for the reaction to occur since there’s no overall gain or loss of electrons. A second study, published a month later in Nature, overturned a long-held belief that radical reactions always destroy a molecule’s 3D shape—the very feature that determines how well a drug binds to its protein target.

“The goal is to make radical cross-coupling so ‘boring’ and routine that no one thinks twice about it,” notes Baran.

Useful chemistry made simple

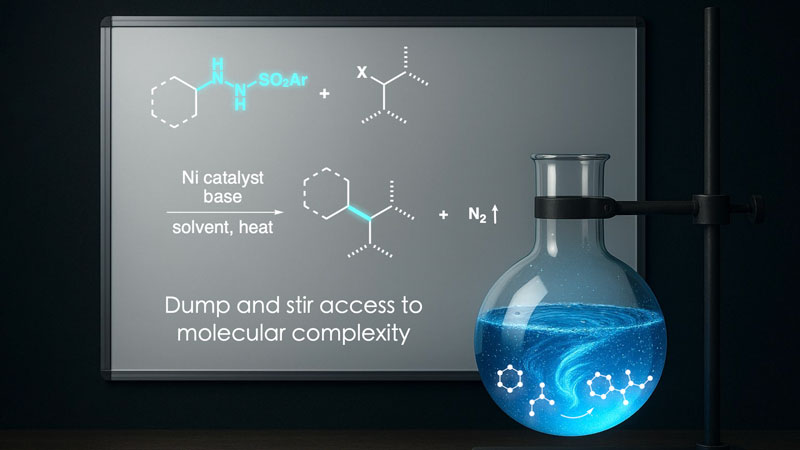

In the first Science paper, Baran’s lab introduced compounds known as sulfonyl hydrazides to the radical cross-coupling process. Unlike traditional radical sources, these substances do double duty: They generate the carbon radicals needed to bond carbon fragments together and donate the electrons required to drive the reaction forward, all without the usual external activators. The upshot is that instead of requiring costly or complicated setups, these reactions can run with simple “dump-and-stir” steps that are no harder than mixing two jars on a benchtop.

“The advantage of a dump-and-stir reaction is that when you scale it up, you don’t need specialized equipment,” points out Baran. “These hydrazides are incredibly simple to make, usually in just one step from affordable alcohols or carbonyls, which are sold commercially.”

Hydrazides’ propulsive force—the clean release of nitrogen gas—is the high energy that makes hydrazine (from the same chemical family) a classic rocket fuel. This force powers the radical cross-coupling reaction without leaving behind the byproducts that render scale-up expensive and cumbersome. It means no need for special light-driven equipment, custom electrochemical cells or excess metal powder. This new simplicity is what makes radical cross-coupling that much more practical, pushing it closer to becoming routine.

“What defines a truly useful chemical reaction?” asks Baran, pointing to the words of his colleague and two-time Nobel laureate Barry Sharpless, who’s also the W.M. Keck Professor of Chemistry at Scripps Research. In the 2001 Nobel lecture for his work on reactions that control a molecule’s 3D shape, Sharpless said, “With respect to chemical reactions, ‘useful’ implies wide scope, simplicity to run, and an essential transformation of readily available starting materials.”

Baran’s radical cross-coupling approach checks all three boxes. The scope is wide, as it connects saturated carbons to other saturated or unsaturated fragments and can even add valuable fluorine-rich groups used in many modern medicines.

“It’s astonishing that this worked on so many different types of bond formation,” remarks Baran. “There are seven new reactions for radical cross-coupling in our paper.”

The setup is straightforward. And the starting pieces—stable sulfonyl hydrazides made from cheap compounds—are ubiquitous.

“Reactions like this make it possible to build more complex molecules faster, with fewer steps and far less waste,” says Jennifer Lafontaine, a Senior Director at Pfizer who leads the company’s Oncology Medicinal Chemistry Group in La Jolla, California. “We’re already putting these radical cross-coupling tools to work in our pipelines at Pfizer.”

Others in the pharmaceutical industry are also embracing Baran’s method.

“This technique holds tremendous promise in transforming the way we approach the synthesis of medicines,” adds Bristol Myers Squibb Scientific Director Michael Schmidt. “The beauty of this approach lies in both the vast number of easy-to-access reactive partners and the simplicity in performing the coupling reaction. Given these characteristics, we’ve seen immediate adoption into our work.”

Cracking the “impossible” to preserve shape

While Baran’s first study laid the foundation for making radical cross-coupling practical, the second Nature paper goes a step further by establishing that the method can preserve its 3D shape, a property known as stereochemistry. This 3D preservation, called stereoretention, is crucial for drug design because even slight changes to a molecule can affect how well it binds to a target and functions in the body.

Baran’s stereoretentive breakthrough draws inspiration from Scripps Research President and CEO Pete Schultz, who demonstrated in his PhD thesis that a molecule called a diazene could release nitrogen gas while preserving stereochemistry—but only in a simple, non-radical reaction. The finding was vital because in drug design, shape is everything. A molecule’s 3D form (specifically, its “handedness,” or chirality) often determines how well it fits a biological target. In chemistry, a molecule is considered chiral if its mirror image can’t be superimposed, like a left and right hand.

However, it was long believed that once a molecule became a carbon-centered radical—typically after a bond breaks and leaves behind an unpaired electron—it would flatten out and lose its 3D shape in trillionths of a second. That meant radicals were considered too wild to preserve stereochemistry, making them unreliable tools for building chiral drugs.

“The textbooks say stereoretentive radical cross-coupling is impossible because radicals are like the Tasmanian Devil and don’t stay put,” explains Baran, admitting he didn’t believe it was feasible either. “You lose their stereochemistry almost instantly.”

What changed his mind was postdoctoral fellow Jiawei Sun—a first author on both studies—being able to retain nearly 40% of the original stereochemistry with a chiral compound just by using the conditions outlined in the first Science paper.

“It was the most exciting and surprising discovery of my career,” says Baran. “Never in my wildest dreams would I have expected that.”

For the second Nature paper, Baran and his team optimized the reaction to keep the radical “caged,” or tethered to a nickel catalyst via a unique diazene intermediate so it couldn’t spin and scramble. In test reactions, the method preserved about 90% of the original chirality—an unprecedented feat in radical chemistry. And crucially, it did so without the need for costly, tailor-made chiral ligands (molecules that steer the reaction to make one mirror-image shape over another) that have bogged down similar attempts for years.

“It’s like catching a tornado in a jar,” describes Baran. “This shows we can build chiral, 3D-rich molecules through radicals without losing what makes them biologically useful.”

For pharmaceutical chemists, it means a faster route to chiral, 3D-rich drug candidates—no more lengthy detours to rebuild a molecule’s stereochemistry after a radical reaction flattens it—saving time, money and materials.

“Achieving this level of stereocontrol with radicals was a Holy Grail. Now it’s within reach for mainstream synthesis,” says Schmidt. “This is the kind of advance that lets us build more sophisticated drug candidates faster, with fewer resources and cleaner chemistry.”

A simple reaction with profound reach

Going forward, Baran and his lab plan to further fine-tune the reaction mechanism so chemists can run radical cross-couplings with better control. They’ve already posted a preprint with the lab of Keary Engle, Scripps Research’s Dean of Graduate & Postdoctoral Studies, on using sulfonyl hydrazides for C–H activation—that is, selectively breaking carbon–hydrogen bonds (which are notoriously strong and unreactive) so chemists can attach new fragments and build complex molecules more efficiently.

“We’re working on direct utility toward medicinal chemistry,” adds Baran.

By taming radical reactions to preserve stereochemistry, Baran’s method could reshape how chemists approach antibiotics, cancer therapies, agrochemicals and advanced materials. His lab has also published a study in collaboration with several pharmaceutical companies to show how these reactions could help attach small, drug-like fragments to larger molecules.

Moreover, Baran’s team is collaborating with the lab of Donna Blackmond, the John C. Martin Endowed Chair in Chemistry at Scripps Research, to demystify the precise mechanism and refine the radical cross-coupling system so it can work with only small amounts of nickel, making the process cleaner, cheaper and more scalable for industry.

“This is a rapidly emerging Scripps Research-wide phenomenon,” emphasizes Baran. “Where we take this further is the next Holy Grail: carbon–carbon bonds that keep their 3D shape even when both fragments—not just one—are complex and saturated.”

But even with these latest advances, the radical future has become a lot more practical—and maybe someday soon, even a little boring.

In addition to Baran and Sun, authors of the study “Sulfonyl hydrazides as a general redox-neutral platform for radical cross-coupling,” are Áron Péter, Jiayan He, Jet Tsien, Haoxiang Zhang, David A. Cagan, Nicholas Raheja and Yu Kawamata of Scripps Research; Benjamin P. Vokits, Michael D. Mandler, David S. Peters, Martins S. Oderinde and Maximilian D. Palkowitz of Bristol Myers Squibb; and Paul Richardson and Doris Chen of Pfizer. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant GM-118176); the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation program for a Marie Skłodowska-Curie postdoctoral fellowship (MSCA-GF grant 101110288); and Nankai University.

In addition to Baran and Sun, authors of the study “Stereoretentive radical cross-coupling,” are Jiayan He, Luca Massaro, David A. Cagan, Jet Tsien, Yu Wang, Flynn C. Attard, Jillian E. Smith, Jason S. Lee and Yu Kawamata of Scripps Research. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant GM-118176); the Gates Foundation (grant INV-056603); a postdoctoral fellowship from the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet, grant VR-2023-00499); and the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Innovation in Peptide and Protein Science for Capacity Building (grant CBG117).

In addition to Baran and Engle, authors of the study “Alkyl sulfonylhydrazide-enabled, chemoselective Ni-catalyzed directed C(sp2)–H alkylation via low-temperature, amine-assisted metalation/deprotonation,” are Shuanghu Wang, David A. Cagan, Yilin Cao and Yu Kawamata of Scripps Research; and Benjamin P. Vokits and Maximilian D. Palkowitz of Bristol Myers Squibb. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant GM-118176); the National Science Foundation (grant CHE-2400359); the Siyuan Postdoctoral Fellowship of Shanghai Jiao Tong University; and the David C. Fairchild Endowed Fellowship of Scripps Research.