How Josh Boyer is bridging research and patient care to advance type 1 diabetes treatment

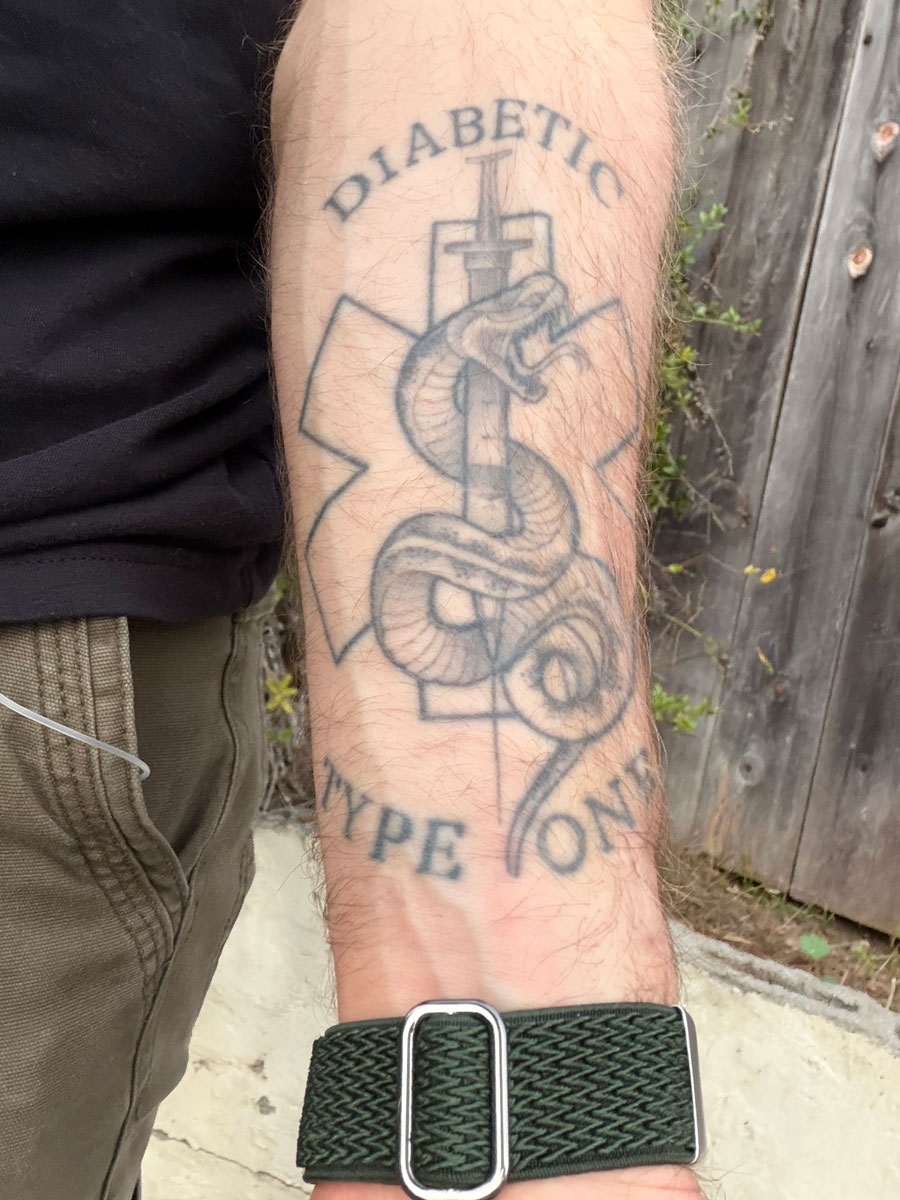

For Scripps Research scientist Josh Boyer, type 1 diabetes isn’t just a research focus—it’s personal. Diagnosed at age five, he’s spent his life navigating the daily demands of managing the condition while channeling his experience into a career. As a nurse, diabetes educator and researcher in Professor Luc Teyton’s lab, Boyer splits his time between patient care and cutting-edge immunology research aimed at deepening scientists’ understanding of type 1 diabetes.

Scripps Research Magazine spoke with Boyer about his journey from patient to advocate to scientist—and why he believes a cure is within reach.

When were you diagnosed, and what was it like to grow up with type 1 diabetes?

I was diagnosed when I was five years old after my parents noticed I was drinking a lot of water and using the restroom frequently. Thankfully, both of my parents worked in medicine, so they immediately recognized these symptoms as classic signs of type 1 diabetes. Managing my diabetes has been a full-time job for our family ever since.

Despite the challenges, my parents worked hard to make my life as normal as possible so that I could participate in typical childhood activities like playing sports. Growing up in the small town of Winona, Minnesota, our family enjoyed an outdoorsy lifestyle that included many hiking and camping trips. Managing my blood sugar on these excursions took extra planning and care, but my parents were dedicated to giving me diverse experiences and not letting my diagnosis hold me back.

A big struggle that I felt was the unwanted attention that comes with type 1. Everyone at school knew I had diabetes because I’d often have to miss class to eat a snack in the nurse’s office. At restaurants, people would stare or ask what I was injecting. There was even a funny period when insulin pumps first came out, when people would ask me if I was carrying a pager.

How did your diagnosis shape your early career in science?

When it came time to decide what I wanted to study in college, I chose biochemistry because of my interest in science and the outdoors. After completing my undergraduate degree at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, I moved to Los Angeles and began working at the UCLA AIDs Institute. While at the institute, I worked on designing gene therapy treatments for HIV, which led to the discovery of my passion for immunology. It was incredible to connect the dots between my research and how my own experience with an autoimmune disease like type 1 could translate into finding a cure.

During my time working in immunology labs, I had the pleasure of getting to know many people with diabetes and was energized by my conversations with them. As I became more aware of the challenges they faced, I realized that I wanted to help people more directly.

I joined the youth leadership council at Breakthrough T1D, a nonprofit dedicated to accelerating life-changing breakthroughs in order to cure, prevent, and treat type 1 diabetes and its complications. One of the highlights was supporting fundraisers like bike races and carrying glucose tablets for participants. I also began teaching group classes for newly diagnosed type 2 patients at the Scripps Whittier Diabetes Institute.

In November 2019, I came across a paper from Scripps Research Professor Luc Teyton and was excited by the work he was doing. Many people with type 1 diabetes are closely engaged with emerging research, and the work from Teyton’s lab was particularly compelling. I reached out to Luc and asked if I could volunteer in his lab to stay close to the research aspect of diabetes, and he offered me a position as a research technician.

Credit: Josh Boyer

What kind of patient education are you working on currently?

I wear a lot of hats in my career these days. Since graduating from nursing school in 2022, I work as a nurse at Sharp Grossmont Hospital in their oncology unit, where I get to interact with patients, keep up my bedside skills and continue to learn about immunotherapy treatments.

I’m also an inpatient diabetes educator at Scripps Health, where I mostly support newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes patients. I work closely with case managers and social workers as well to support diabetes patients who are homeless or have mental health issues. As someone who believes that everyone deserves good diabetes care, I address concerns that uniquely affect underserved populations, like how to keep insulin cool if the patient is homeless or how to connect them to support groups.

Credit: Josh Boyer

What are you investigating in Luc Teyton’s lab?

Even with my busy schedule, I enjoy working in Luc’s lab because of his unique approach to studying type 1. Recently, our team published a paper on a new, rare cell type near the pancreas that we believe contributes to type 1 onset. Called vascular-associated fibroblastic cells (VAFs), they act as molecular peacekeepers in the pancreas—actively protecting insulin-producing cells from the immune system. We found that when VAFs encounter high levels of inflammation, they can’t do their job—triggering autoimmunity. This was an interesting finding that could help us develop therapies that protect or restore VAF function.

Our group was also recently awarded two grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), which will help us continue to explore how VAFs work and use bioengineered models to track the initiation and progression of the disease.

What do you hope the future looks like?

I’m optimistic that there’s a cure in our lifetime. Basic research like what we’re doing at Scripps Research is essential because the more we understand about which cells initiate the attack and when, the better positioned we’ll be to develop both treatment and prevention.

While we work on a cure, however, I want to encourage diabetes patients not to be afraid to reach out for help from diabetes educators like me to help achieve their goals. My message to diabetes patients is that although diabetes management can be tough—know you’re not alone and that there’s a community here to support you.