Irene Khalek is on a quest to design a universal antivenom and protect people around the world from the deadliest snakebites.

Across cultures, countries and mythologies, snakes are often associated with rebirth and renewal, as well as danger and deception. When you hear about the Mozambique spitting cobra in Southern Africa that fires venom into eyes and bites people in their sleep, it’s no surprise that many fear, as well as revere, these animals.

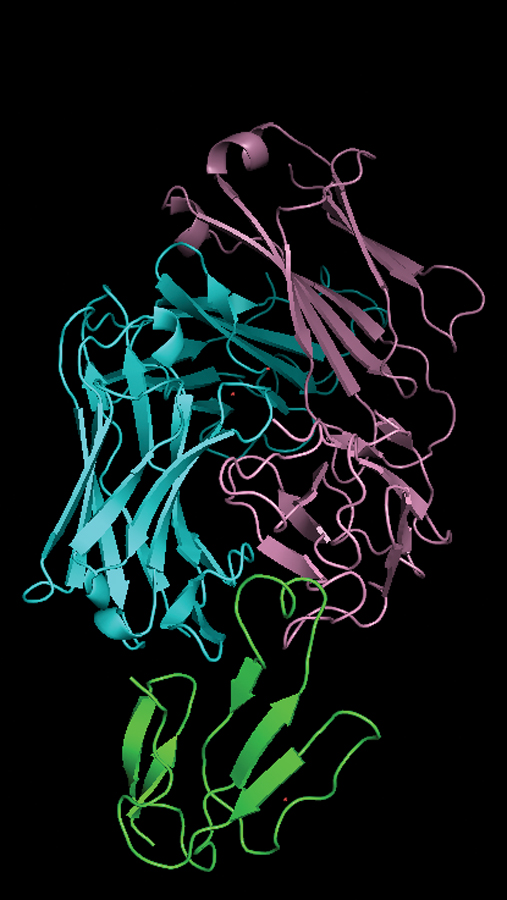

and blue) bound to three-finger

toxin (green)

Credit: Yen Thi Kim Nguyen, Scripps Research

While most snakes are significantly less frightening than this example, there are still roughly 100,000 people a year who die from venomous snakebites. Those who do survive often lose limbs or are otherwise disfigured. Currently available antivenoms have remained unchanged for the last century, are still composed of polyclonal antibodies extracted from large animals, are expensive to manufacture with a short shelf life, and each one is typically effective against only a single snake species. This is all life-threatening news for victims of venomous bites.

Irene Khalek, PhD, a staff scientist in the Jardine lab at Scripps Research, is determined to change that. Khalek is designing a universal antivenom, one that could protect against all medically relevant snakebites.

“Our therapeutic goal is to design a next-generation antivenom that’s as universal as possible—one that’s more potent, safe and reliable when compared with the current model of animal-derived antivenoms,” she says. “Today, if you get bitten and envenomated, you need multiple vials of highly expensive antivenom injected in a hospital setting that often cause additional adverse reactions. It can save your life, but you really don’t want it unless you absolutely need it.”

Khalek didn’t expect her career would lead to working with the world’s most lethal snake venoms. After enjoying biology and chemistry classes in high school, she knew she wanted to pursue something in the STEM field. This is what led her to MIT, where she received her bachelor’s degree in materials science and engineering, and then a master’s degree in biomedical engineering.

(Naja naja)

Credit: Kartik Sunagar

That all changed when she was searching for a new position four years ago after completing her PhD in biomedical sciences at UC San Diego and her postdoctoral research in human performance muscle physiology at California State University, Fullerton. Between the exciting drug discovery aspect and the opportunity to work on a fascinating yet neglected disease, the antivenom job posting immediately piqued her interest.

The position was at IAVI’s Neutralizing Antibody Center at Scripps Research—an organization primarily focused on developing a universal HIV vaccine. This may seem like a vastly different undertaking than creating an antivenom, but Khalek explains that’s not the case.

“It’s a similar problem over a different span of evolutionary time: You have many different variants of the same snake toxin or viral protein, but each has a conserved site that allows the toxin or the virus to modulate a certain protein or enter a human cell,” she says. “It’s then our job to find the antibodies that target that conserved site found across all toxins or all viral mutations.”

The Jardine lab transitioned from IAVI to Scripps Research in 2023, including Khalek. Her research focus remains the same as the team continues to investigate their antibody “cocktail” approach. This means combining multiple, fully human monoclonal antibodies that could protect against different snake venoms, from cobras to vipers and every medically relevant snake in between. It’s as complicated of a project as it sounds—the type of antibodies Khalek is after are incredibly rare, requiring the screening of billions of clones to find ones fully capable of neutralizing multiple toxin variants.

Credit: Kartik Sunagar

“Our therapeutic goal is to design a next-generation antivenom that’s as universal as possible—one that’s more potent, safe and reliable when compared with the current model of animal-derived antivenoms,”

—Irene Khalek, PhD

Those special proteins are called broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs). By targeting components in the venom that are shared across multiple snake species, the idea is that a bnAb cocktail could bind to—and thus, intercept—many different venom types.

“Beforehand, we didn’t know the sequences for any of the antibodies in existing antivenoms that work against the toxins,” she adds. “So, we’re now doing the hard work of discovering and actually characterizing them.”

Recently, Khalek and others in the Jardine lab have proven this approach works. Published in Science Translational Medicine in 2024, they successfully found antibodies that could protect against a highly lethal toxin found in the venom of all elapids, the group of deadly snakes that includes mambas, cobras, taipans and kraits.

The antibodies they discovered target three-finger toxins—proteins that cause full-body paralysis after a bite. They’re named for the three “finger-like” loops that make up their structure. In the study, Khalek and her colleagues engineered an innovative platform to produce these toxins recombinantly in enough quantities for their experiments, and then screened them against billions of different human antibodies to uncover which ones bound to all the toxin variants and neutralized them the best. Eventually, they found their match: an antibody they refer to as 95Mat5.

With this proof-of-concept in hand, Khalek is now investigating a different snake toxin found in both elapids and vipers called phospholipase A2 (PLA2), which exerts both neurotoxic and cytotoxic effects, including necrosis. Her staff scientist colleague, Laetitia Misson Mindrebo, is pursuing antibodies against snake venom metalloproteinase (SVMP), a major component of viper venom that causes deadly hemorrhage. The hope is that the team can identify additional antibodies that tightly bind PLA2 and SVMP similar to how 95Mat5 targets the three-finger toxins, and eventually combine these into a cocktail that could protect against all major snake species.

“The question is still out there: Is it possible to find a broadly neutralizing antibody for every major toxin? And how many do we ultimately need in that cocktail?” Khalek says.

Khalek and her colleagues aren’t alone in answering these questions. They’ve been partnering with other scientists around the world in their quest to develop an antivenom—combining the Jardine lab’s expertise in bnAbs and protein engineering with their collaborators’ extensive knowledge in snake venoms.

“Bringing some of the more advanced, newer technologies for antibody discovery has been well-received, as we closely collaborate with people in labs across the U.K., Europe and India who are much more experienced in toxins, snakes and that specialty,” she says.

When Khalek isn’t at the lab bench investigating snake antivenoms, she spends much of her time with her family, including her husband, two-year-old son, and another child shortly on the way. And while she’s interested in the snakes she’s studying, she prefers it from the comfort of her own lab: “I’ve really enjoyed learning about the snakes themselves, even though I’d like to avoid handling them or getting too close,” she says.