An interview with Scripps Research postdoctoral associate, Ee Phie Tan

Ee Phie Tan credits her time in the lab with keeping her young—and that’s not just because she studies how to extend lifespan and treat age-related diseases. A postdoctoral associate at Scripps Research, Tan finds the very process of research energizing and her role mentoring younger scientists reminds her how to remain creative and fresh in her approach to science.

“I’m really enthusiastic about my research, “she says. “I find being a scientist so incredibly rewarding.“

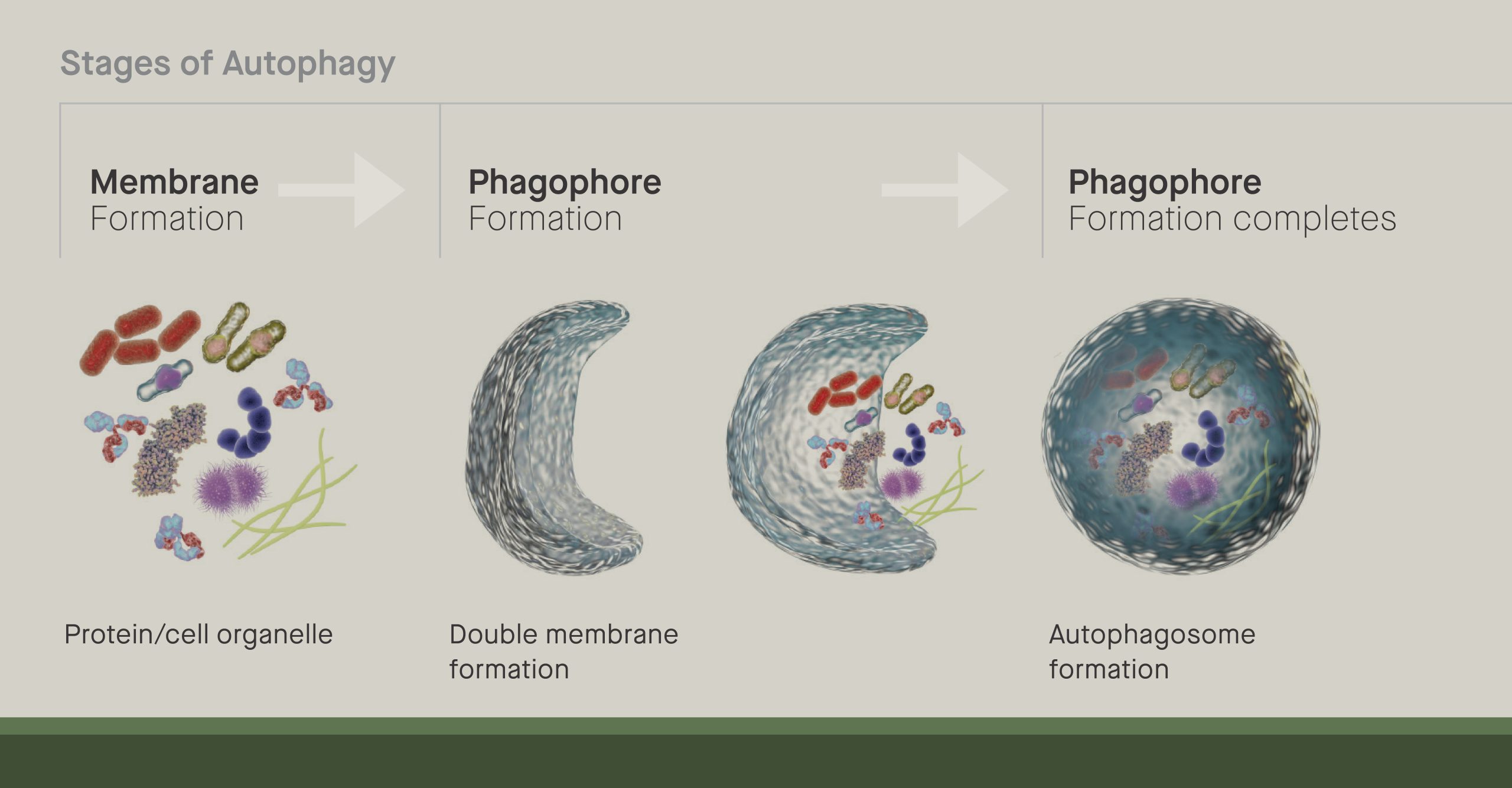

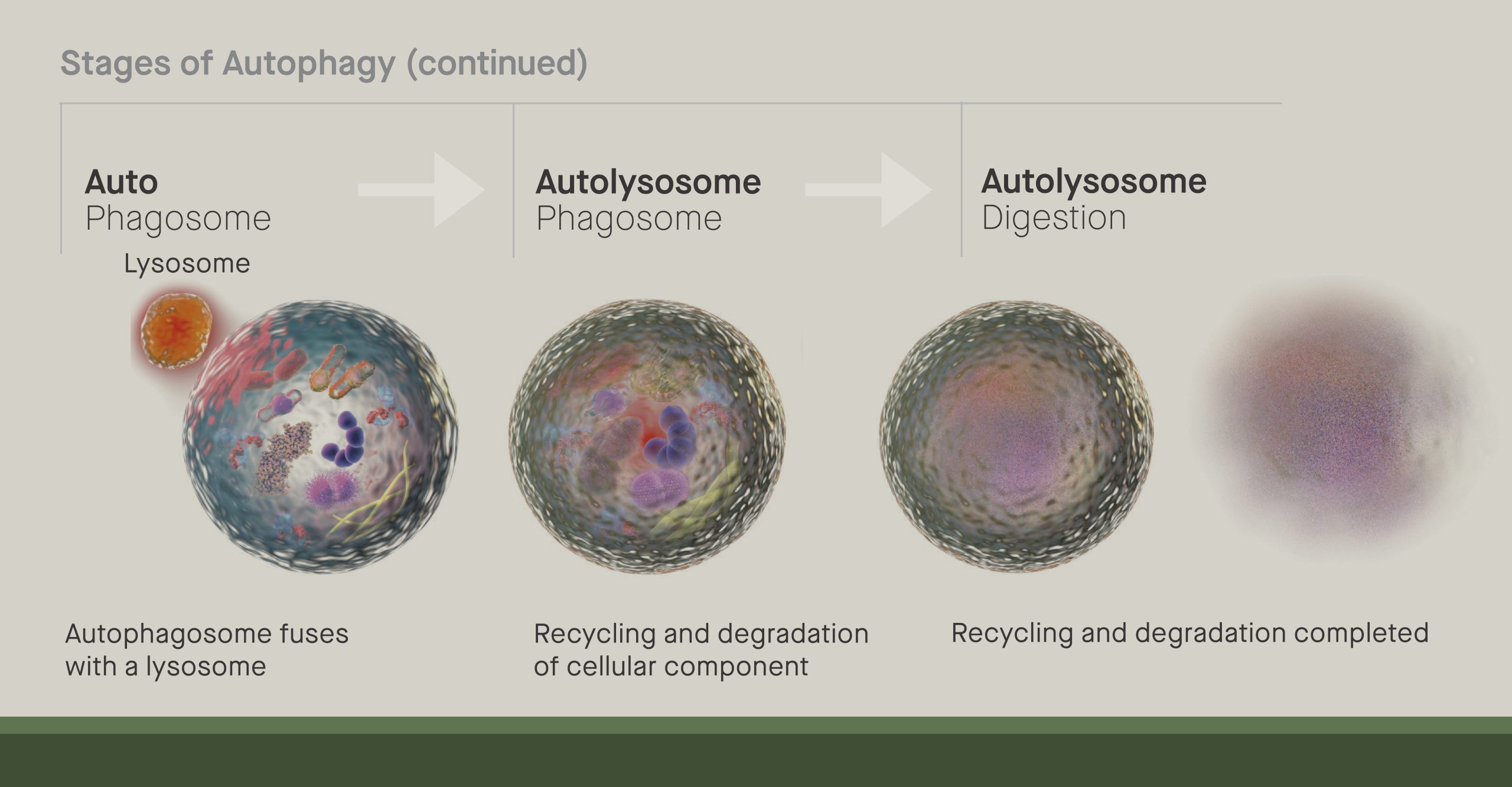

Tan, who joined the lab of Scripps Research professor Jeffery Kelly, looks at how cells recycle lipids— a class of molecules including fats, oils and hormones. Studies have suggested that the recycling of molecules inside cells, a process known as autophagy, becomes less effective as people age. This then leads to the accumulation of cellular trash, and in turn, can contribute to diseases ranging from Alzheimer’s to cancer.

“Imagine one day the trash truck stops coming down your street,” says Tan. “Your neighborhood is going to start stinking, and nobody is going to be happy. This is like what happens in aging cells.

“Tan, who grew up in Malaysia, didn’t always want to be a scientist. She instead dreamed of being a doctor, and signed up for pre-med classes as a freshman at the University of Iowa. But Tan needed a job, and as an international student, it was hard to find one she qualified for. When she finally found a part-time gig washing glassware in a lab, she was thrilled for the extra pocket money. Little did she know that the lab would become her home away from home and launch her into a new career path.

Tan realized that biomedical research could, ultimately, let her cure disease in a different way than if she were to become a clinician.

“I still wanted to be in the medical field, and I still wanted to help people. This was another way of doing it,” says Tan. “A lot of the progress in medicine today relies on basic research.”

In 2011, Tan joined the brand-new University of Kansas lab of Chad Slawson, first as a research assistant and then, after some coaxing, as his first graduate student. There she studied how sugar modifications on proteins can change their functioning—and contribute to disease.

Tan’s interest was particularly piqued by a collaboration with a neurologist at the University of Kansas, Russell Swerdlow, to study how changes in sugar modifications might contribute to Alzheimer’s disease. She became fascinated by the molecular underpinnings of neurodegenerative diseases and aging. So, when it came time for a postdoctoral fellowship, Tan joined the Sanford Burnham Prebys lab of Malene Hansen, who studies autophagy in aging. Tan’s aim in the lab was to pinpoint proteins that were recruiting lipids into the cellular recycling machinery. This might help develop new ways to boost this recycling capacity in diseased cells, Hansen and Tan reasoned.

Around the same time Tan began this work, Kelly’s lab at Scripps Research was screening drugs for their ability to help cells remove excess lipids. One of the compounds the lab identified, dubbed A20, was related to autophagy and overlapped with the pathways that Tan was already studying. With Tan at the helm, the Kelly and Hansen labs launched a collaboration to study the drug. They showed that not only does the drug help cells remove lipids but—in C. elegans worms—it extends lifespan by 20 to 30%.

When Malene Hansen got an offer to move her lab across the country, Tan felt situated in San Diego (after just buying a house), and the move to Kelly’s lab felt natural. Without missing a beat, she shifted to a postdoctoral position at Scripps Research in 2021 and continued her research on A20. She discovered that, if autophagy is blocked, A20 no longer extends C. elegans’ lifespan. This complements findings from others in the field showing that autophagy is required in diverse paradigms of lifespan extension. Tan and her colleagues also found that A20 can reverse the accumulation of lipids in neurons affected by Alzheimer’s disease. Now, they’re testing whether that translates to a change in how the diseased neurons function.

“It’s only recently that researchers have discovered that, in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients who have passed away, there are a lot of lipid deposits,” says Tan. “We don’t know yet what role this plays in disease, but we think that removing these aggregates could help treat it.”

When Tan’s not at the lab bench, she’s active in the scientific community as a mentor and leader: She was president of her graduate student organization, has co-chaired a postdoctoral association and will be fellow chair of next year’s international Women in Autophagy Symposium. “To me, leadership is not just applicable to entrepreneurship or running a company; I think a lot of the same skills are required in running a lab too,” she says. “I take on leadership roles because I want to practice my communication, help people around me grow and expand my network.”