with Katja Lamia

Katja Lamia, a professor in the Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology and an associate dean of the Skaggs Graduate School of Chemical and Biological Sciences at Scripps Research, says that contrary to popular belief, the body doesn’t have just one internal clock—it has many. In fact, almost every type of tissue and organ has its own circadian rhythm: an internal timekeeping system that oscillates throughout the day. This system governs fluctuations of cellular protein production in a 24-hour period and other timeframes. From the brain to the liver, each body part follows its own schedule. Circadian rhythms control various physiological processes—such as metabolism, hormone levels and sleep patterns—and they can have detrimental effects, like tumor formation, when out of sync.

Lamia, who’s been studying circadian rhythms for nearly two decades, has received several honors for her research, including the Curebound Discovery Grant, the Aschof’s Rule Prize, the Kimmel Scholars Award from the Sidney Kimmel Foundation, and the Searle Scholars Award from the Kinship Foundation. But Lamia wants her work to go a step further. She hopes that harnessing knowledge of circadian rhythms will aid in the development of new drugs and ensure that timing is considered in treatment plans. Scripps Research Magazine spoke with Lamia to learn more about her background, misconceptions about circadian rhythms, and how our internal clocks dictate the rhythm of our lives.

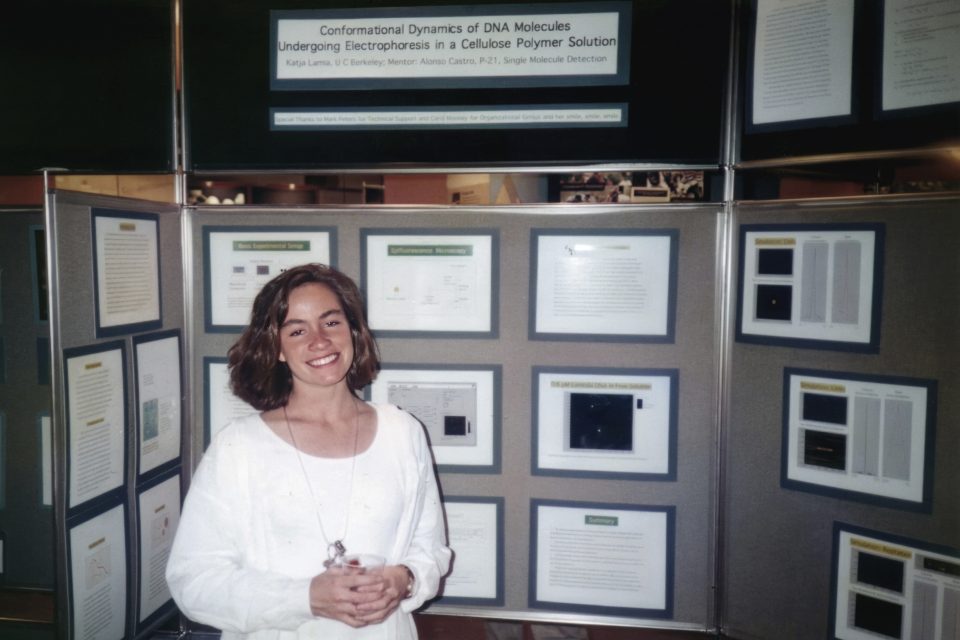

After studying biophysics in graduate school, what inspired you to research circadian rhythms?

The most well-recognized circadian rhythm is the sleep-wake cycle, but what I’m really interested in—and what my lab at Scripps Research focuses on—is how the molecular clocks that drive the sleep-wake cycle also drive all kinds of physiological processes.

During my first year in graduate school, I read articles about circadian clocks, which I’d never heard of before. There was growing recognition that circadian clocks are not only driving sleep-wake cycles but are also present in all organs. The big question was: What are they doing in those places? That’s when I decided to study circadian biology as a postdoctoral researcher.

Moreover, I was interested in how the time of day affects metabolism and whether circadian clocks were involved, which we now know is true. Your metabolism varies throughout the day and is controlled by circadian clocks in different organs—they all have these clocks intrinsic to their cells. For example, liver function changes depending on the time of day, and it’s influenced by a clock that exists in every cell of the organ. Since the liver’s circadian rhythm affects how food and drugs are metabolized, it’s important to think about when to eat or take medication.

What are the main challenges of researching circadian rhythms?

The research entails doing every experiment multiple times because you need to conduct each one at different times of the day. Of course, there are methods to help enable this in the lab. You can set up experiments with different lighting schedules, for instance, so you don’t have to stay awake through the night to carry out experiments at many different time points. But even with those mechanisms in place, the research still requires several replications. That’s why it’s so important to be very careful, even if you don’t use multiple timepoints—you might not get consistent experimental outcomes if you’re not paying attention to the time when you’re doing your experiments.

What specific projects related to circadian rhythms are you working on at Scripps Research?

My lab primarily studies genetic changes that impact the circadian clock. We try to understand why specific molecular changes would affect circadian rhythms and make someone more likely to be a night owl versus an early bird. We’re also interested in understanding why the long-term disruption of circadian rhythms—like what happens with shift work—is detrimental to health. And now, we’re doing more research related to cancer biology. The risk for many types of cancer has increased in shift workers, but it’s unclear why. There’s evidence that the disruption of the immune system’s circadian rhythm is a contributing factor.

Cancer isn’t a single disease—there are so many tumor types, and they’re completely different from each other. Disruption of circadian rhythms increases tumor formation in various kinds of cancer, including that of the lungs. We published a paper in Science Advances showing that circadian disruption similar to what shift workers experience caused a large increase in lung tumor formation. However, this isn’t universally true. We also published a paper last year in F1000Research showing that the same type of circadian disruption didn’t impact a lymphoma model. Now, we’re in the process of publishing a study in which we looked at molecular circadian rhythms in tumors and found that they’re not disrupted in kidney cancer, whereas they are disrupted in several other cancer types.

Which discovery are you proudest of?

I was among the first people to recognize and show that circadian clocks in peripheral tissues—so in places like the liver—play an important role in regulating metabolism. When I started working on related research 20 years ago, some scientists responded with scorn and said the idea was ridiculous. But today, everybody knows it’s true.

I’m also proud of the discoveries from my lab at Scripps Research. We examine how circadian rhythms regulate metabolism and cancer, and a lot of basic research that we’ve done has set the groundwork for looking at how responses to drug treatments might differ depending on the time they’re administered. One of the first papers published from my lab was work I started as a postdoctoral researcher at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies and finished here. It showed that molecular and physiological responses to steroid hormones like glucocorticoids varied at different times of the day. And now, other groups have looked at using steroid hormones for conditions like muscular dystrophy. They’ve demonstrated that treatment timing can make a big difference in outcomes.

What future impact would you like your research to have on society?

Frequently changing schedules cause circadian disruption and adversely affect health, so I’d like to understand why shift workers are at increased risk for metabolic disease and cancer. I also want to help improve conditions for shift workers. Related research has changed policy and improved shift-work schedules, but there’s still so much that we don’t understand well because there are so many different professions where shift work is necessary: You need police working around the clock, pilots crossing time zones, and emergency medical care available 24/7. So how do we optimize schedules to minimize the health impact on those individuals?

We need to examine not only the exact timing of shifts but also the working conditions of those shifts. Take light exposure, for instance. Different wavelengths of light have different health effects. And having less light exposure during the day or more exposure at night are both associated with detrimental consequences for health. So perhaps we could improve conditions for workers by changing the spectrum of light that they’re exposed to during their shifts.

What are the greatest misconceptions about circadian rhythms?

It’s amazing how the public has become much more aware of circadian biology over the past 20 years. When I started working in this field and said that I researched circadian biology, most people had no idea what I was talking about. Today, a lot of individuals have heard of circadian rhythms, but many still think circadian rhythm is all about sleep and don’t recognize that it affects every aspect of health. Metabolic pathways, cell growth, and the body’s response to DNA damage are all directly controlled by these rhythms.

It’s also important to understand that each person is different. “Early to bed and early to rise makes a man healthy, wealthy and wise” doesn’t apply to everyone. There are individual differences related to how much sleep you need and when you should sleep. Genetic changes that influence circadian rhythms could make someone more likely to be either an extreme night owl or an extreme early bird. That’s called your chronotype, which is your natural behavioral activity schedule. There’s a lot of evidence that people who are naturally night owls tend to do better when they work later. So just because somebody goes to bed late and wakes up late doesn’t mean they’re lazy—especially when it comes to teenagers.

Speaking of teenagers, how do circadian rhythms change throughout life?

There are well-established patterns of how chronobiology changes with age. Therefore, many states are moving high school start times later because most teenagers naturally have a later circadian activity rhythm than adults. Research shows that high school students perform better when they start school later in the day, and that’s because their chronotype makes it hard for them to go to sleep and to wake up earlier. So, when you have early class times for high schoolers, they’re going to be sleep deprived.

I have a funny story about that from when I was in 11th grade: I slept through my physics class every single day. It wasn’t on purpose—but it was after lunch, which is when my exhaustion would kick in. We had a math teacher auditing the class who would sit in the back of the room, and I always sat in front. She once told my mom, “Your daughter is so attentive in class; while everyone else is chitchatting, she’s sitting there in the front row quietly paying attention.” But the truth is, I was sound asleep. It was probably for the best because I really needed that rest during the day, and then I could study at night when I was actually awake.

How has knowledge of circadian rhythms influenced your personal habits?

I pay more attention to getting sufficient sleep, even though trying to balance work, family and everything else sometimes makes it difficult. But I’m more aware of the importance of sleep, and I have more respect for my own natural rhythms. Also, being aware of research related to light exposure and how it plays such an important role in maintaining circadian rhythms and health has changed my daily behaviors. I now make sure to get adequate light exposure during the day and not too much light exposure at night. These changes have directly affected my lifestyle for the better.